I don’t expect anyone to read this, but it needed to be written…

This week is a strange one for me. I’ve written before about how odd the annual anniversary of my surgery is, and how peculiar it always feels to remember back to an age when I was so poorly. This year I feel it more keenly than ever, as it marks a decade since an unassuming medical team at a local hospital saved my life.

At the time I knew things were bad, but had no idea quite how serious. Even now, looking back it’s all a topsy-turvy mess of memories and ridiculously warped perceptions. I recall how normal that alien situation eventually became – how necessity drove myself and my family to perceive some astonishingly awful trials as everyday occurrences, because in their familiarity they had become casual routine.

At fourteen years old I identified more with some of the younger parents than I did with the infants with whom I shared a hospital ward. Though deteriorating daily and desperate to go home, on one ward I spent my time chatting to a young mum whose toddler-daughter had been admitted following complications from her diabetes. I don’t remember her name, but I think the little girl was called Rebecca. The mother was young and had been raised within the mistrustful culture of many poorer cities, so was vary of the doctors and health visitors who had been trying to help her. The more she struggled with her daughters’ illness, the more help they tried to offer her, and the more worried she became that they’d take her Rebecca into care if they discovered she wasn’t coping. I remember long conversations where she’d tearfully recount the occasions when she had hidden in her flat with the little girl, trying to keep her quiet because a social worker was at the door, and the mother was scared even to let them in. They’d been alerted by the hospital because the pair had missed several paediatric check-ups. Rebecca’s mother said that the reason she had missed the check-ups were that she couldn’t always afford the bus fare to get her daughter to the hospital. Rather than asking for help, she had grown more and more fearful of displaying any weakness, lest it be used against her. After a few days of talking her round, and promising her that social services would be able to help her get to the hospital, and wouldn’t take her daughter away, the little girl was discharged and her mother promised me she’d take advantage of the help that was being offered.

A week later when Rebecca came to the hospital for a check-up her mother came to the ward with chocolates for me, her relief evident, the burden lifted somewhat from shoulders only a few years older than mine. She finally found the courage to break away from the scaremongering whispers of the council estate she grew up on, and allowed to social workers to visit her home and chat to her about her daughter. Together they’d sorted out the benefits she was entitled to, and helped her arrange travel for the little girl to the clinic.

I recount this because I remember it more clearly than I recall many of the details about my own circumstances. There was so much information buzzing about the place, so many people coming in and out, and so much crap to deal with (in both literal and less literal senses) that focusing on trying to make a difference became a way to derive some purpose from it all. My father reacted similarly to the situation, staying with me at the hospital the 9 weeks I was there, but putting in more hours than ever as unofficial social worker, grief counsellor and therapist for the many exhausted and struggling parents whose children were my contemporaries.

All the while time was ticking. We didn’t really know how fast at the time; not even the doctors knew how close I was going to come to being beyond their assistance. As I said, so much became normal that I stopped complaining about the pain, I just learned to get on with it. Daily rituals became learning opportunities for me and for the staff, who were more used to caring for younger children and made the most of the opportunity to finally converse with an articulate guinea-pig. They all wanted to know if I could feel the crushed tablets going down the nasa-gastric tube, and what the high-calorie feed tasted like, if I could taste it at all? I vividly remember the strange coldness as they’d flush the pills down with clean cold water to avoid the tube blocking, and the weird release of pressure following a little extra force when it did block, which made my stomach gurgle and made the gentle nurses wince.

My life revolved around various escape plans. Most days that meant that I would have my Dad or other visiting family take me down to the canteen where we’d try and spot presenters and producers from City Hospital, with whom we all became quite friendly. Other times it meant sitting in the Burger King in the hospital foyer, trying to collect all the Pokemon toys and dreaming up schemes to claim the most-coveted Pikachu. (Which we knew was selling for a lot of money on Ebay but could never persuade the staff to let me have.) Even if it was freezing cold I’d insist on going out to the fish-pond outside the main entrance, where I’d sit and nibble home-made sandwiches brought in by my Nan; throwing the fat, ethereal koi carp more than I ever ate myself, and occasionally chucking in a penny with a wish. The main escape plan however was a burning desire to go home – a desperate need which found me sobbing and desolate on more occasions than any physical suffering ever did. I made it home twice during that long stay, once for 14hrs, and the second time only for 7. Each time I’d persuaded the doctors that I was feeling a bit better and they’d given in to my begging to go home. Each time my condition worsened drastically from just the effort required to leave the hospital, and I was rushed back in by ambulance. The last of those times I remember what a treat it was to be pushed around our small local Tesco in a red cross wheelchair, picking out the food I’d been craving while incarcerated on the Children’s Ward. I’d been on a high-calorie diet for months and was encouraged to eat all the things most children are strictly rationed, but hospital food was forever lacking in flavour or nutrition, and the canteen also had its limitations. The meal I chose for my dinner was a puff pastry chicken pie; a pre-hospitalisation favourite and one I had missed the most during a brief period on a milk-free diet where pastry was forbidden. So pleased was I to sit down to this highly-anticipated meal that I – unusually – devoured my portion with gusto, enjoying my food for the first time in almost two years, without worrying about the pain and sickness which would, inevitably, follow. I was devastated when it made me just as ill as I had been when admitted to hospital in the first place, because not only did it seem a cruel denial of something I had been looking forward to, but it was a very difficult defeat for someone as stubborn as myself to accept.

It was then that I knew, regardless of the doctors’ hopes and my own determination to be fine, that observation and maintenance was no longer enough. They needed to intervene and operate, despite the dangers of the surgery and the massive and invasive nature of the operation and its aftercare. Such a drastic step was it to request such a course of treatment that my doctor had me assessed by a pair of psychologists who had to certify that I did indeed understand the gravity of the situation and wasn’t looking for an “easy way out”. I knew it was dangerous, and I was as scared as anyone is when they face something so uncertain, but I also felt deep in my bones that it was necessary. I was exhausted, but more than that, I knew we had exhausted all the other options, and I didn’t have what it took to try them all again when they’d had no effect. I’d borne the difficulty of the 20hr per day tube feeds to keep my weight viable, and tolerated the 60-plus tablets I took each day, but no more. It had kept me alive, barely, but that just wasn’t good enough any more. So eventually, they operated. It wasn’t until later I found out that when they had opened me up things were worse than they had realised. Because I’d grown accustomed to managing the pain and other awful symptoms, they’d failed to spot just how far my condition had worsened. We were told that if they hadn’t operated when they did, I would have deteriorated so much within the next few days that the operation wouldn’t have done any good. Discovering that I came so close to losing my life before I’d even had the chance to take charge of it has always felt slightly unreal. I think I have always felt a little detached from that particular aspect because I was at an age where every teenager feels invincible, immortal, and had never lost anyone close to me. I had no understanding of death, let alone any comprehension of my own threatened mortality. I had known that dying was a possibility, but saw it as something which could happen – if all else failed – but I never believed that the doctors would fail. With every unsuccessful treatment followed the presentation of another. More tablets, a different diet, more invasive tests. It was a relentless merry-go-round but never one I had considered finite. The thought that they would eventually run out of ideas was one which never really resonated with me. Doctors were clever, authoritative figures who made people better. They’d always managed to sort me out before. Being the product of a school system where the people in charge are omniscient, omnipresent beings who must be obeyed meant that I didn’t question the ability of those in charge of my case then. Providing I did as I was told I would get better. And I did as I was told most of the time. I argued with the doctors when they refused to explain treatment plans to me satisfactorily, but compromised in the end. Bar the occasional tablet flushed down the sink or thrown out of the window in exasperation (I blame myself for a generation of mutant pigeons on the south coast) I complied with every round of treatment eventually. Which was why they finally operated, despite the risks, when I asked them to. It proved to be a far from easy option, but one I cannot regret because it saved my life.

When sorting through paperwork recently I stumbled across some poems my father wrote while we were living in the hospital. Some of them are too personal and too heart-wrenching for me to reproduce here, but because they set the tone of the period more than anything I can rattle off, I will share a couple of them.

Tears flowing silently

Down slowly reddening cheeks.

Emotions contained and hidden

Bursting forth from within

Like a watery volcano.

Rivulets streaming across a rounded landscape,

Pouring silently over the crevice edge,

Falling to the floor below.

An outpouring of grief,

Unexpected yet necessary,

To promote day to day survival

And encourage strength to continue.

Not distressing, and without shame,

Just…natural.

© Dave Lawrence 2000

I still believe that the whole experience was much harder on the people who love me than it ever was for me myself. I was so overwhelmed by the daily grind of the circumstances and the struggle needed just to live at that time that I didn’t have the opportunity to be distracted by the fear which so consumed them.

I’ve relayed a lot of information about nothing in particular, and it doesn’t do justice to the desperation of the situation I was in then, but then I am not the sort of person to wallow in the worst moments of my life. It’s not easy to escape, especially at this time of year, but that doesn’t mean it has to rule my every moment during other times. While I wish my family hadn’t had to experience the incomprehensible lows and feelings of helplessness that my illness presented them with, and while I often regret the things my adolescent illness prevented me from accomplishing, I can’t wish it away entirely. I am the person I am because of the experiences I have endured. The saying “What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger” is a tawdry cliché, but one which has some genuine application here.

By many peoples standards I have done little with the last decade of my life. I’ve not travelled extensively and am not at the peak of a career. I’ve not begun building a family of my own like so many of my peers, and also had to forgo my ambitions regarding higher education. I still live with the fallout of such major illness even today, and the issues which have followed continue to frustrate and challenge me. But I’ve been published in almost as many books as there have been years since the operation, written features for many different magazines and websites, petitioned the government for better health education in schools. I’ve guested on a panel advising on patient welfare, begun designing my own range of jewellery and learning how to manufacture it. I’ve also collected a glorious, varied and astonishing group of friends and dazzling acquaintances, and have stumbled through adolescence making many of the same mistakes as everyone else, and coming out the other side just as screwed up as the next person and twice as flawed – but still generally pretty pleased with the person I am because of it all.

Most importantly, I survived. I’ve had ten years which I nearly didn’t get, and regardless of the challenges I’ve faced and the limitations I am still wrangling with, that is a remarkable achievement in itself.

The second of my father’s poems captures the spirit of the attitude we were all left with better than anything I could say to end. So I will finish by saying that I will never be able to thank my amazing Dad enough for supporting me through the worst of times, despite him battling his own anguish, and will always be grateful to him and my Nan, Grandad, auntie and friends for all they did to help keep me sane (ish) and as positive as possible during a part of my life we were all struggling to accept and understand.

Nothing is as precious as time.

Each moment of our very existence

Is to be savoured, not wasted.

No-one is so prophetic

As to know what lies in wait,

How time can be lost,

And once gone

Is gone forever.

Live and enjoy,

Use every second, every breath

To make the most

Of time on the planet,

As when it is past

It can never be recovered.

© Dave Lawrence 2000

Wednesday, 13 October 2010

Friday, 14 May 2010

The Importance Of Being Idle

It’s M.E Awareness Week, and one group of sufferers is organising a march to highlight their campaign for more research into the illness. While I support the cause, I can’t help but think they’ve failed to fully consider the implications of their chosen fundraising method. With a strategy straight off’ve The Apprentice, they’re urging sufferers of M.E/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome to join their mini-marathon, to draw attention to the difficulties faced by people who are often so tired their mobility is restricted. Next week I hear they’re helping out with the sponsored Archery at the local School for the Blind…

The Guardian has attempted to do their bit by publishing two articles about M.E/CFS. The first flits between being so incomprehensibly scientific that the majority of their readership wouldn’t bother to look past the first paragraph, to denouncing M.E campaigners as radical nutcases. There’s very little worthwhile information in the article, which basically tells people that an American charitable trust believes M.E/CFS is caused by a retrovirus, but that independent and governmental scientists have failed to replicate their findings. It’s amazing just how much they managed to write about the fact that they’re still none the wiser – but following the assisted suicide of Lynn Gilderdale by her mother Kay, Chronic Fatigue Syndrome is still a hot-topic.

During the trial and the accompanying peak in media-interest, I was infuriated by the ignorant and incredibly biased coverage, which presented it as a terminal illness, or disease with no hope or potential for management. This is, of course, ridiculous. I’m a living testament to the fact that it is entirely possible to be certifiably-knackered and yet still make enough of a nuisance of myself in the world for my life to have some meaning. Lynn Gilderdale’s case was extreme, but her desire to end her life stemmed from a terrible depression, which was influenced by – not the sole result of – her M.E. Since her tragic case (extremely rare in terms of severity) hit the news earlier this year, I had yet to hear a medical or media professional make any of those points clear. In the first of the guardian articles “The Trouble With ME”, amidst the irrelevant information and radical opinion, one consultant does offer some sensible thoughts:

“Alastair Santhouse, consultant in psychological medicine at the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust, was deeply concerned by much of the press coverage, which depicted ME/CFS as a terminal illness and wrote to say so in the British Medical Journal. "It was being talked about in terms of the euthanasia/assisted suicide debate," he said. "It is an awful illness – chronic, unpleasant and very isolating – but it is not a terminal illness. There are treatments available and they are not perfect but we as a profession should not be giving up on people.”

The second of their articles is billed as a “first person account of living with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome” but is misleading for its brevity, though with the best of intentions.

The truth about life with M.E/CFS is a little more balanced – which of course is often far too dull for the British media! Yes, there are dramatic lows, which would probably elicit a couple of hundred pounds from Take A Break magazine if every desolate detail were exploited in full. It just wouldn’t be a very fair picture of life with M.E/CFS, which is the thing sadly lacking from the illnesses recent surge in popularity.

I began having clear problems with fatigue ten years ago when I was just 14, and failed to recover as expected from the serious illness which had blighted the previous two years of my life. No one could understand why I wasn’t showing signs of improvement when I should have been, and it became clear that the fatigue wasn’t simply a symptom of medical-malaise, but was a distinct issue in-and-of itself. M.E/CFS is more than just fatigue, it is a collection of rather nondescript symptoms which vary from person to person, but are very much centred around being incredibly tired.

The fatigue is a soul-crushing exhaustion, the like of which I have never experienced as the result of a long, hard day. It isn’t the sort of tiredness you get after a terrible day at work, or even after an extra-tough slog in the gym. It’s a mental and physical weariness more akin to the debilitating weakness you feel when you have a really bad case of the flu, or the worst hangover you can imagine – only without any of the fun the night before! The fatigue is complicated by severe aches and pains, which make muscles tremble and bones feel like they burn alternately with fire and ice. Also headaches, confusion, inability to concentrate, nausea, sensitivity to light, dizziness, lack of apatite, poor memory, and a raft of other issues mean that to some extent every day has to be negotiated through that fluey-fog. What marks out a good day is the ability to do normal things in spite of it, because it fades enough to be manageable after a few hours of being awake. On a very bad day, it doesn’t fade at all. Next time you wake up on a cold day, feeling rough, and you are so desperate to go back to sleep that – for a few seconds – you honestly can’t envision how you will drag yourself out of bed, imagine what it would feel like if that desperation lingered all day. If there was no way to shake it off with a shower, or a bit of willpower. How would your life change, if that overwhelming need for slumber was the overriding feeling for more than a few minutes, and you couldn’t muster the physical or mental energy to move yourself out of bed even if it were on fire around you?

That’s what most M.E/CFS sufferers have to contend with every day, some for a few minutes, and some for weeks or months at a time. I consider myself lucky that, in general, only the first hour or two of every day is like that for me. On a bad day when it doesn’t recede, I’ve known it take half an hour before I can force myself out of bed – which might not sound like much, but trust me, it’s really annoying on a day when you wake up needing a wee!

All that, when viewed on its own, quite obviously makes life incredibly difficult, but that’s not the whole story. Yes, it certainly makes even the most mundane day-to-day living more of a challenge, but does not make everything impossible. People are adaptable creatures, it’s what has helped us colonise the planet and remain at the top of the food chain for millennia; growing and expanding as we develop new skills and behaviours. Such is life for someone with M.E. For every symptom that creates issues, there’s a creative solution being implemented by somebody. Plenty of people manage a variety of incapacities without allowing their lives to grind to an agonizing halt. Amputees use wheelchairs or prosthetic limbs, ugly people get jobs on the nightshift, and those with M.E/CFS find ways to work around their constant fatigue. Tiredness this severe is a disability, but not a hopeless one. Admittedly, at its worst there is nothing to be done but surrender to it and rest – but at other times a moderate approach allows for far more normality than many people would envisage. Many sufferers have families, many others manage to hold down jobs - they just do it all with that fluey-fog lingering overhead, finding ways to get around the difficulties they face when their illness clashes with their aspirations or responsibilities.

The best explanation for the energy-compromise we all make is “The Spoon Theory” – written in the early part of the century by Lupus sufferer Christine Miserandino. (It can be read online here, and I really, really recommend it.) The condition she has is different, but the management is the same. People with M.E/CFS have a limited number of units of energy per day, and even the smallest tasks cost units. Getting out of bed? 1 unit. Showering? Another unit. Getting dressed, hair and makeup, making breakfast, eating breakfast, watching morning telly… All individual units expended before you’ve even left the house in the morning. Once you’ve used up your full reserve of energy, that’s it. You’re exhausted and couldn’t do anything else even if you had the mental energy to want to - which, if you’ve run out of units, you simply don’t. Most people begin each day without knowing exactly what they’re going to do, open to the possibility of spontaneous ideas or activities. Those with M.E/CFS don’t have that luxury, or at least not without having to trade off on the other things we might have planned to do.

I manage my fatigue by working from home, having a laptop not a PC, being incredibly anti-social when going through a bad patch, and taking to my bed to rest whenever possible like a spoilt Victorian aristocrat. I know that if I have a busy day ahead, I have to rest up the day before, and write off the day after, in much the same way others would prepare for a marathon drinking session to celebrate a birthday. You know you’ll pay for it after, but that’s a compromise you decide you’re willing to make.

All of that adds to the complexities we are all faced with when going about our lives, but it certainly doesn’t mean life is in any way “over”. Unfortunate as it is that there are people like Lynn Gilderdale who never find a way to live with their symptoms, they are in the minority, and the message that it is possible to have a life and a disability is one that needs better representation in contemporary media. Until we understand the causes of M.E/CFS, the least we should do is report a balanced take on the consequences faced by the people living with it.

Now I’m off to lie down, because I used up a unit writing this blog post, and have to have a rest before I can get my lazy backside downstairs to make the cup of tea I am yearning for. (Yes, this was as much of an endurance-test to write as it was to read). On second thoughts, as you'll be needing tea of your own, you can make mine too. Go on! It’s M.E Week! I’m the centre of attention here. Me, Me, Me, Me, Me.

The Guardian has attempted to do their bit by publishing two articles about M.E/CFS. The first flits between being so incomprehensibly scientific that the majority of their readership wouldn’t bother to look past the first paragraph, to denouncing M.E campaigners as radical nutcases. There’s very little worthwhile information in the article, which basically tells people that an American charitable trust believes M.E/CFS is caused by a retrovirus, but that independent and governmental scientists have failed to replicate their findings. It’s amazing just how much they managed to write about the fact that they’re still none the wiser – but following the assisted suicide of Lynn Gilderdale by her mother Kay, Chronic Fatigue Syndrome is still a hot-topic.

During the trial and the accompanying peak in media-interest, I was infuriated by the ignorant and incredibly biased coverage, which presented it as a terminal illness, or disease with no hope or potential for management. This is, of course, ridiculous. I’m a living testament to the fact that it is entirely possible to be certifiably-knackered and yet still make enough of a nuisance of myself in the world for my life to have some meaning. Lynn Gilderdale’s case was extreme, but her desire to end her life stemmed from a terrible depression, which was influenced by – not the sole result of – her M.E. Since her tragic case (extremely rare in terms of severity) hit the news earlier this year, I had yet to hear a medical or media professional make any of those points clear. In the first of the guardian articles “The Trouble With ME”, amidst the irrelevant information and radical opinion, one consultant does offer some sensible thoughts:

“Alastair Santhouse, consultant in psychological medicine at the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust, was deeply concerned by much of the press coverage, which depicted ME/CFS as a terminal illness and wrote to say so in the British Medical Journal. "It was being talked about in terms of the euthanasia/assisted suicide debate," he said. "It is an awful illness – chronic, unpleasant and very isolating – but it is not a terminal illness. There are treatments available and they are not perfect but we as a profession should not be giving up on people.”

The second of their articles is billed as a “first person account of living with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome” but is misleading for its brevity, though with the best of intentions.

The truth about life with M.E/CFS is a little more balanced – which of course is often far too dull for the British media! Yes, there are dramatic lows, which would probably elicit a couple of hundred pounds from Take A Break magazine if every desolate detail were exploited in full. It just wouldn’t be a very fair picture of life with M.E/CFS, which is the thing sadly lacking from the illnesses recent surge in popularity.

I began having clear problems with fatigue ten years ago when I was just 14, and failed to recover as expected from the serious illness which had blighted the previous two years of my life. No one could understand why I wasn’t showing signs of improvement when I should have been, and it became clear that the fatigue wasn’t simply a symptom of medical-malaise, but was a distinct issue in-and-of itself. M.E/CFS is more than just fatigue, it is a collection of rather nondescript symptoms which vary from person to person, but are very much centred around being incredibly tired.

The fatigue is a soul-crushing exhaustion, the like of which I have never experienced as the result of a long, hard day. It isn’t the sort of tiredness you get after a terrible day at work, or even after an extra-tough slog in the gym. It’s a mental and physical weariness more akin to the debilitating weakness you feel when you have a really bad case of the flu, or the worst hangover you can imagine – only without any of the fun the night before! The fatigue is complicated by severe aches and pains, which make muscles tremble and bones feel like they burn alternately with fire and ice. Also headaches, confusion, inability to concentrate, nausea, sensitivity to light, dizziness, lack of apatite, poor memory, and a raft of other issues mean that to some extent every day has to be negotiated through that fluey-fog. What marks out a good day is the ability to do normal things in spite of it, because it fades enough to be manageable after a few hours of being awake. On a very bad day, it doesn’t fade at all. Next time you wake up on a cold day, feeling rough, and you are so desperate to go back to sleep that – for a few seconds – you honestly can’t envision how you will drag yourself out of bed, imagine what it would feel like if that desperation lingered all day. If there was no way to shake it off with a shower, or a bit of willpower. How would your life change, if that overwhelming need for slumber was the overriding feeling for more than a few minutes, and you couldn’t muster the physical or mental energy to move yourself out of bed even if it were on fire around you?

That’s what most M.E/CFS sufferers have to contend with every day, some for a few minutes, and some for weeks or months at a time. I consider myself lucky that, in general, only the first hour or two of every day is like that for me. On a bad day when it doesn’t recede, I’ve known it take half an hour before I can force myself out of bed – which might not sound like much, but trust me, it’s really annoying on a day when you wake up needing a wee!

All that, when viewed on its own, quite obviously makes life incredibly difficult, but that’s not the whole story. Yes, it certainly makes even the most mundane day-to-day living more of a challenge, but does not make everything impossible. People are adaptable creatures, it’s what has helped us colonise the planet and remain at the top of the food chain for millennia; growing and expanding as we develop new skills and behaviours. Such is life for someone with M.E. For every symptom that creates issues, there’s a creative solution being implemented by somebody. Plenty of people manage a variety of incapacities without allowing their lives to grind to an agonizing halt. Amputees use wheelchairs or prosthetic limbs, ugly people get jobs on the nightshift, and those with M.E/CFS find ways to work around their constant fatigue. Tiredness this severe is a disability, but not a hopeless one. Admittedly, at its worst there is nothing to be done but surrender to it and rest – but at other times a moderate approach allows for far more normality than many people would envisage. Many sufferers have families, many others manage to hold down jobs - they just do it all with that fluey-fog lingering overhead, finding ways to get around the difficulties they face when their illness clashes with their aspirations or responsibilities.

The best explanation for the energy-compromise we all make is “The Spoon Theory” – written in the early part of the century by Lupus sufferer Christine Miserandino. (It can be read online here, and I really, really recommend it.) The condition she has is different, but the management is the same. People with M.E/CFS have a limited number of units of energy per day, and even the smallest tasks cost units. Getting out of bed? 1 unit. Showering? Another unit. Getting dressed, hair and makeup, making breakfast, eating breakfast, watching morning telly… All individual units expended before you’ve even left the house in the morning. Once you’ve used up your full reserve of energy, that’s it. You’re exhausted and couldn’t do anything else even if you had the mental energy to want to - which, if you’ve run out of units, you simply don’t. Most people begin each day without knowing exactly what they’re going to do, open to the possibility of spontaneous ideas or activities. Those with M.E/CFS don’t have that luxury, or at least not without having to trade off on the other things we might have planned to do.

I manage my fatigue by working from home, having a laptop not a PC, being incredibly anti-social when going through a bad patch, and taking to my bed to rest whenever possible like a spoilt Victorian aristocrat. I know that if I have a busy day ahead, I have to rest up the day before, and write off the day after, in much the same way others would prepare for a marathon drinking session to celebrate a birthday. You know you’ll pay for it after, but that’s a compromise you decide you’re willing to make.

All of that adds to the complexities we are all faced with when going about our lives, but it certainly doesn’t mean life is in any way “over”. Unfortunate as it is that there are people like Lynn Gilderdale who never find a way to live with their symptoms, they are in the minority, and the message that it is possible to have a life and a disability is one that needs better representation in contemporary media. Until we understand the causes of M.E/CFS, the least we should do is report a balanced take on the consequences faced by the people living with it.

Now I’m off to lie down, because I used up a unit writing this blog post, and have to have a rest before I can get my lazy backside downstairs to make the cup of tea I am yearning for. (Yes, this was as much of an endurance-test to write as it was to read). On second thoughts, as you'll be needing tea of your own, you can make mine too. Go on! It’s M.E Week! I’m the centre of attention here. Me, Me, Me, Me, Me.

Tuesday, 23 March 2010

Painting By Numbers

In an overdue bid to mark World Poetry Day (celebrated on the 21st March) here's the press-shot from the Valentine's Big Screen shenanigans outlined in my previous entry. (I'm the pallid looking creature in the pink scarf, and this photo illustrates both my dislike of daylight illumination against my blueish-white Twilight-tan, and the face that my face always freezes into the least flattering grimace whenever there is a camera present.)

As you can see it was rather a motley crew of local women participating in the event, though I think that had more to do with the format (love poems) and the fact that it was the middle of the working day on a Tuesday afternoon. While I'd like to say that only the creme-de-la-creme were selected for press participation as part of some elaborate marketing strategy championing fiery-female literature, it's more likely that schoolgirls, retirees, pensioners, council workers from the offices neighbouring the square, and my unemployable self were the only ones available at such short notice.

The poem that was originally adapted into an animated image for the Big Screen event was a crown cinquain titled By The Light. I've always struggled to write on demand - and have even more difficulty practising any economy with words when it comes to any of my writing; be it a hastily scribbled post-it alerting passers-by of the fridge to an unexpected deficit of cat food, a blog post, or an article for a magazine. Abusing my allocated word count and my readers' patience has been a stumbling block since the days of school-essays, and cinquains force me to write outside of that familiar, comfortable style.

A cinquain is a five-line poem with a very strict syllable count; two syllables in line 1, four in line 2, six in line 3, eight in line 4, and two again in line 5. A butterfly cinquain (another favourite in this style) repeats that pattern, but inverted. A crown cinquain such as the one featured here repeats the 2,4,6,8,2 structure five times.

Those very strict parameters are the reason I find it both a challenge and a joy to write cinquains. These poems require endless editing and sculpting to fit within the constraints of the style - constantly snipping down my preferred verbose similes and wildly meandering metaphors until all that remains is enough skeleton imagery and emotion for the readers own imagination to flesh out. This is always an incredibly daunting task for a writer who seeks solace in literary loquaciousness, but is equally thrilling for my inner logophile, and is an excuse to crack open my mental thesaurus. (That sounds like I keep a disturbed dinosaur around to help me find alternative words, which though not my current editing method, does sound like more fun than that irritating paperclip who lurked around Microsoft Word on all the computers at school.) There is also something charming about the purity and simplicity of cinquains that appeals to me. Without having to worry about making sense of any self-imposed rambling structure, I find myself free to really focus on the imagery at hand, while also challenging the importance of every word. It's an entirely different perspective for me, as so much of my work relies on the swirling rhythm of the overall piece, with far less emphasis on many of the words used to create it. My usual manner of poetry is literary pointillism - becoming clearer as the details blend. Cinquains necessitate an opposite approach, and it is this polarity which first attracted me to the style.

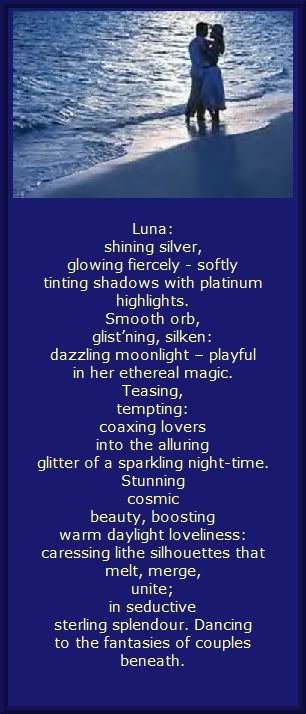

That is all a rather dreadfully technical dissection of this piece's creation, and possibly makes for a terrible introduction to a poem which - while pleasingly elegant - could hardly be described as substantial. Here it is however, presented as was required for a commission last year, with the image that inspired it.

Copywrite K Lawrence 2009

If you've suffered through this much of the blog, your name is automatically entered onto next years' list of proposed recipients for the animal* version of the Victoria Cross, for bravery and endurance beyond the call of duty.

(*Even my influence has its limits.)

As you can see it was rather a motley crew of local women participating in the event, though I think that had more to do with the format (love poems) and the fact that it was the middle of the working day on a Tuesday afternoon. While I'd like to say that only the creme-de-la-creme were selected for press participation as part of some elaborate marketing strategy championing fiery-female literature, it's more likely that schoolgirls, retirees, pensioners, council workers from the offices neighbouring the square, and my unemployable self were the only ones available at such short notice.

The poem that was originally adapted into an animated image for the Big Screen event was a crown cinquain titled By The Light. I've always struggled to write on demand - and have even more difficulty practising any economy with words when it comes to any of my writing; be it a hastily scribbled post-it alerting passers-by of the fridge to an unexpected deficit of cat food, a blog post, or an article for a magazine. Abusing my allocated word count and my readers' patience has been a stumbling block since the days of school-essays, and cinquains force me to write outside of that familiar, comfortable style.

A cinquain is a five-line poem with a very strict syllable count; two syllables in line 1, four in line 2, six in line 3, eight in line 4, and two again in line 5. A butterfly cinquain (another favourite in this style) repeats that pattern, but inverted. A crown cinquain such as the one featured here repeats the 2,4,6,8,2 structure five times.

Those very strict parameters are the reason I find it both a challenge and a joy to write cinquains. These poems require endless editing and sculpting to fit within the constraints of the style - constantly snipping down my preferred verbose similes and wildly meandering metaphors until all that remains is enough skeleton imagery and emotion for the readers own imagination to flesh out. This is always an incredibly daunting task for a writer who seeks solace in literary loquaciousness, but is equally thrilling for my inner logophile, and is an excuse to crack open my mental thesaurus. (That sounds like I keep a disturbed dinosaur around to help me find alternative words, which though not my current editing method, does sound like more fun than that irritating paperclip who lurked around Microsoft Word on all the computers at school.) There is also something charming about the purity and simplicity of cinquains that appeals to me. Without having to worry about making sense of any self-imposed rambling structure, I find myself free to really focus on the imagery at hand, while also challenging the importance of every word. It's an entirely different perspective for me, as so much of my work relies on the swirling rhythm of the overall piece, with far less emphasis on many of the words used to create it. My usual manner of poetry is literary pointillism - becoming clearer as the details blend. Cinquains necessitate an opposite approach, and it is this polarity which first attracted me to the style.

That is all a rather dreadfully technical dissection of this piece's creation, and possibly makes for a terrible introduction to a poem which - while pleasingly elegant - could hardly be described as substantial. Here it is however, presented as was required for a commission last year, with the image that inspired it.

Copywrite K Lawrence 2009

If you've suffered through this much of the blog, your name is automatically entered onto next years' list of proposed recipients for the animal* version of the Victoria Cross, for bravery and endurance beyond the call of duty.

(*Even my influence has its limits.)

Friday, 12 February 2010

Fame and Misfortune

Yesterday I was rather rudely woken by a phone call from the council. Usually this would be reason enough to throw the phone out of the window, refuse to pay my taxes, and chain myself to a local MP until they apologised for all the heinous crimes the government has committed. (Top of the list being the war, I know waking me up would only come a close second.) This time, however, the call turned out to be a rather welcome surprise.

Two weeks ago local poets were asked to contribute love poems to a special Valentines Day exhibition, to be displayed on a big screen in the town centre. I didn't really have anything that I considered to be suitable for a family audience. The first 'romance' poem I ever wrote was about a prostitute at the Moulin Rouge, and the most recent - which was published in an anthology just before Christmas - was described by the first person who read it as making an "almost pornographic" use of metaphor. So, not holding out any hope of it being accepted as 'lovey-dovey enough', I sent in a piece I wrote in the summer of last year. It was inspired by a photo of a couple on a moonlit beach, and indulges itself in detailing the soft, seductive glow of lunar lighting on young lovers. I heard nothing back, and assumed that it had been discarded, because subtle amour hardly ever has a place in commercial Valentines events.

When Craig (or to give him his full title, The Man From The Council) rang me, I was told that the piece would not only be included in the exhibition, but that the Big Screen project is run by the BBC, who had to approve all the entries put forward by the council. It was then that he asked me if I could pop down to the town centre on Friday, because the local newspaper want to run a little Valentines Day feature on the exhibition.

So once again, I have accidentally wound up with a little more than I bargained for!

This is where the poetry will be screened on Sunday 14th February between 12pm and 2pm.

Unfortunately, though a rather rag-tag band of poets turned up to do the interview, the reporter got held up. The photographs were taken, but in the absence of the article I suggested that Mr Council Man Craig get consent from the contributors to have their work printed in the paper. That way the News get their valentines poetry feature, and the council get some publicity for their big screen event. We'll see if it materialises...

The day wasn't a complete waste of time, however, as my Max Clifford coup aside, I also met a couple of people from a local performance poetry group that I'd stumbled across a few days ago. The group meet once a month in a local pub, and mix open-mic poetry readings with live music, which sounds great, and certainly warrants closer investigation at their next event!

I wasn't surprised The News didn't show up for the interview, as they've been busy all day covering the latest step to regenerate the High Street. Today was the launch of a new homewares store on the site of the old Woolworths, which had lain empty since the company went into administration. Now former-Woolworths employees have set up "Alworths" in its place, and my stepbrother - who is now working there - was on hand to help them out with the grand opening!

It's good to know they're equal opportunities employers, isn't it?

It's not only the local news which has been busy of late, as I was also deeply saddened to hear in yesterdays National coverage about the death of a remarkable man; the fashion designer Alexander McQueen. Alexander McQueen was one of the most creative people in fashion, certainly within his generation. His catwalk designs were a spectacle - and whether or not you liked his shows, his talent and imagination was undeniable. He was a really ordinary sort of man; quiet and unassuming until broached about a subject on which he was passionate, and once riled he was well known for being outspoken and reckless. That said, he was never a poseur or a pretentious diva like so many in the fashion industry - or the celebrity circuit as a whole. He was the sort of Londoner you walk past in the street every day, or hang out with in the pub.

Despite his earthy roots, his innovative approach to colour, shape and style within fashion completely redrew the boundaries for catwalk shows, and he created some truly beautiful pieces of "art". Many wonder why the death of a glorified tailor is such big news, but they underestimate Alexander McQueen's impact on British culture and style. With a list of revered celebrity clients, and a reputation for eccentric genius, he may not have made the headlines of every newspaper - but you can bet he's dressed many of the people who did, and his inspiring outfits were often the reason they'd made the news in the first place!

Had his medium been paint and canvas, or film and CGI he would be considered an artist. Just because he created his masterpieces out of fabric and leather, doesn't make the loss of his astonishing imagination and daring eccentricity any less great.

McQueen's life in pictures from The Guardian

Besides, the man made the kind of shoes I'd sell my soul for.

The news also provided me with another 'nanecdote' this week, when the teatime coverage of the woman who killed her lover by poisoning his curry, prompted the following conversation with my much-quoted Nan.

Newsreader: "Mr Cheema, known as 'Lucky' was left blinded and paralysed before he died..."

Nan: "What did they say people called him?"

Me: "His name was 'Lakhvinder'. They said his nickname was 'Lucky'."

Nan: "Why do they call him lucky?! He can't have been that lucky if he was murdered!"

Me: "Well I think they called him lucky before he was murdered. I doubt they've started calling him that since he died."

Nan: "Oh, well, it doesn't really matter. Poor man's dead now. ...I've never much liked the idea of curry, you know."

So there you have it. It's fine to have mental ex-girlfriends who try to poison you when you move on with your life, just steer clear of spicy food, for it will be your downfall.

While I'm scribbling this, I want to wish a very happy birthday to my other elderly friend, Anna, whose youth was finally ripped kicking and screaming from her clutches today.

Not sure what her excuse was before, but now she's hit her 'flirty thirties' Steve Thompson had better sleep with one eye open. ...And shower with the door locked when she's at Burnley's ground. Actually he should probably just have his kit on already under his clothes, and not shower until he gets home. To a place with CCTV. And lots of alarms...

Two weeks ago local poets were asked to contribute love poems to a special Valentines Day exhibition, to be displayed on a big screen in the town centre. I didn't really have anything that I considered to be suitable for a family audience. The first 'romance' poem I ever wrote was about a prostitute at the Moulin Rouge, and the most recent - which was published in an anthology just before Christmas - was described by the first person who read it as making an "almost pornographic" use of metaphor. So, not holding out any hope of it being accepted as 'lovey-dovey enough', I sent in a piece I wrote in the summer of last year. It was inspired by a photo of a couple on a moonlit beach, and indulges itself in detailing the soft, seductive glow of lunar lighting on young lovers. I heard nothing back, and assumed that it had been discarded, because subtle amour hardly ever has a place in commercial Valentines events.

When Craig (or to give him his full title, The Man From The Council) rang me, I was told that the piece would not only be included in the exhibition, but that the Big Screen project is run by the BBC, who had to approve all the entries put forward by the council. It was then that he asked me if I could pop down to the town centre on Friday, because the local newspaper want to run a little Valentines Day feature on the exhibition.

So once again, I have accidentally wound up with a little more than I bargained for!

This is where the poetry will be screened on Sunday 14th February between 12pm and 2pm.

Unfortunately, though a rather rag-tag band of poets turned up to do the interview, the reporter got held up. The photographs were taken, but in the absence of the article I suggested that Mr Council Man Craig get consent from the contributors to have their work printed in the paper. That way the News get their valentines poetry feature, and the council get some publicity for their big screen event. We'll see if it materialises...

The day wasn't a complete waste of time, however, as my Max Clifford coup aside, I also met a couple of people from a local performance poetry group that I'd stumbled across a few days ago. The group meet once a month in a local pub, and mix open-mic poetry readings with live music, which sounds great, and certainly warrants closer investigation at their next event!

I wasn't surprised The News didn't show up for the interview, as they've been busy all day covering the latest step to regenerate the High Street. Today was the launch of a new homewares store on the site of the old Woolworths, which had lain empty since the company went into administration. Now former-Woolworths employees have set up "Alworths" in its place, and my stepbrother - who is now working there - was on hand to help them out with the grand opening!

It's good to know they're equal opportunities employers, isn't it?

It's not only the local news which has been busy of late, as I was also deeply saddened to hear in yesterdays National coverage about the death of a remarkable man; the fashion designer Alexander McQueen. Alexander McQueen was one of the most creative people in fashion, certainly within his generation. His catwalk designs were a spectacle - and whether or not you liked his shows, his talent and imagination was undeniable. He was a really ordinary sort of man; quiet and unassuming until broached about a subject on which he was passionate, and once riled he was well known for being outspoken and reckless. That said, he was never a poseur or a pretentious diva like so many in the fashion industry - or the celebrity circuit as a whole. He was the sort of Londoner you walk past in the street every day, or hang out with in the pub.

Despite his earthy roots, his innovative approach to colour, shape and style within fashion completely redrew the boundaries for catwalk shows, and he created some truly beautiful pieces of "art". Many wonder why the death of a glorified tailor is such big news, but they underestimate Alexander McQueen's impact on British culture and style. With a list of revered celebrity clients, and a reputation for eccentric genius, he may not have made the headlines of every newspaper - but you can bet he's dressed many of the people who did, and his inspiring outfits were often the reason they'd made the news in the first place!

Had his medium been paint and canvas, or film and CGI he would be considered an artist. Just because he created his masterpieces out of fabric and leather, doesn't make the loss of his astonishing imagination and daring eccentricity any less great.

McQueen's life in pictures from The Guardian

Besides, the man made the kind of shoes I'd sell my soul for.

The news also provided me with another 'nanecdote' this week, when the teatime coverage of the woman who killed her lover by poisoning his curry, prompted the following conversation with my much-quoted Nan.

Newsreader: "Mr Cheema, known as 'Lucky' was left blinded and paralysed before he died..."

Nan: "What did they say people called him?"

Me: "His name was 'Lakhvinder'. They said his nickname was 'Lucky'."

Nan: "Why do they call him lucky?! He can't have been that lucky if he was murdered!"

Me: "Well I think they called him lucky before he was murdered. I doubt they've started calling him that since he died."

Nan: "Oh, well, it doesn't really matter. Poor man's dead now. ...I've never much liked the idea of curry, you know."

So there you have it. It's fine to have mental ex-girlfriends who try to poison you when you move on with your life, just steer clear of spicy food, for it will be your downfall.

While I'm scribbling this, I want to wish a very happy birthday to my other elderly friend, Anna, whose youth was finally ripped kicking and screaming from her clutches today.

Not sure what her excuse was before, but now she's hit her 'flirty thirties' Steve Thompson had better sleep with one eye open. ...And shower with the door locked when she's at Burnley's ground. Actually he should probably just have his kit on already under his clothes, and not shower until he gets home. To a place with CCTV. And lots of alarms...

Saturday, 9 January 2010

Happy-Slapped by a Gastroenterologist

Welcome to the first blog entry of 2010. I wonder how many blogs this month have begun with variations on that introduction? I'll try to be more original in future - without resorting to the gratingly-zany wackiness of the Rowntrees Randoms advert. If I ever try and begin a banana with a random postman then you have my permission to pour custard on my cherry tomatoes. ...For anyone unfamiliar with the ad in question - who now thinks I'm still hung-over from New Years' - watch this codswallop:

Following a lovely Christmas with the newly-reconfigured family, nasty colds meant that many of us saw in the New Year with bugs that probably warrant their own X-file. I'm not a patient patient, and my cold was always much worse at night than during the day - leading to many a comparison between myself and one of the Gremlins (post midnight-snack.)

Being unwell on holidays really shouldn't be tolerated. In the same way the French protested against wheel clamping by injecting superglue into the lock of every contraption they happened across, Mother Nature should be forced to rethink; as each and any one of us shoves an Olbas inhalator up the nose of every passerby who sniffles within our reach.

My unseasonal malaise began just before Christmas, when I had to attend a routine check-up at the hospital. Due to a family history of Ulcerative Colitis (and a personal one come to that), I'm required to undergo cancer/abnormal-cell screening every couple of years. Now, it's never pleasant, but always necessary - and means letting a strange man get closer to me with a camera than even Paris Hilton would allow...

Honestly, people complain about CCTV, and "living in a Big Brother Orwellian State" but they haven't the faintest idea just how much of a liberty SnappySnaps and Co. actually take. Some things just ought not be captured on film; like any time Les Dennis or Keith Chegwin take their clothes off, or the inside of my remaining digestive tract. Colonoscopies are like clinical happy-slapping: inflicting pain on camera. Gregarious film critic Mark Kermode calls it "torture-porn" when they do so in movies, but I really don't think that what they do to me biannually is for anyone's gratification.

Ever since watching the BBC's season of charming Alan Bennett monologues, I can't help but read these more mundane of my ramblings in his distinctive kitchen-sink-drama voice. I have at least one acquaintance who finds Bennett inexorably dull, which probably lends itself better to the comparison than I have the right to seek in any other respect.

Due to a lack of inspiration - and indeed motivation - to write of late, I've found myself falling back in love with an old flame. What is the object of my re-ignited passion? ...Jewellery design.

Although as a dedicated logophile words will always be my first love, I must admit to several illicit affairs with various aspects of colour, shape and form. From a pre-pubescent love of photography, to an adolescent admiration for design, I have always enjoyed the creative process of weaving something that did not exist until I saw how it should be. All my writing stems from very similar origins, and my enjoyment of literary and fashionable pursuits have long jockeyed for position. Usually the two work reasonably well in tandem. I am flighty, and tire of projects easily, so when I become disillusioned with one outlet for my imagination, I've always been glad of the other to fall back on.

Writing is the one I could not live without - I'm far too opinionated and narcissistic not to have some journalistic outlet - but my eye for colour and unusual shapes means that design is very important to me too. It's a natural part of the way I interact with the world - I see it as an artist, albeit not one of any groundbreaking insight.

Professionally, there is very little opportunity to write at the moment, and apart from my usual poetic outlets, I've been lacking in productivity. Some poets can sit and write about any given subject 'on demand' - will themselves into a mindset where their talent is readily accessible. I, however, have never mastered that skill. While all creation - be it within science or the arts - is a somewhat magical affair, instead of being an alchemic recipe for new life and ideas, mine is far more of a New Age bastardization of Paganism. I don't mix all the ingredients and come up with something astonishing - I must just hang around on the second Tuesday of the full moon wearing red knickers, and wait for a word, or an idea to spark something into being. As the full moon this month was on a Wednesday and my red kecks were in the wash, no sparks flew. So back to jewellery design it is.

As the company I was involved with before have cut so many of its staff, I am not in the position I was previously of being able to design exquisitely expensive pieces and submit them to a workshop for manufacture. For a while at least, I will be back to making the items myself. Hopefully it will give me the chance to expand my silver and goldsmithing abilities, as I get back into manufacture as well as design. Gemmology is a subject I retain a highly-geeky knowledge of, and a return to jewellery design is an exciting prospect.

If and when I launch a few items online, it will be via an Etsy store, and I will announce the details and promotional codes here, so that those of you who suffer my ramblings have some form of compensation for so doing. So watch this space! ...Not literally. It could be a while, and if you just sit there watching then I'll end up being reported to Watchdog as the person responsible for your deaths - like the DJ who challenged his listeners to drink as much water as they could, and one of them died. While inciting such idiots to follow their natural instincts is not a crime I believe to be too heinous, nonetheless it's not the sort of publicity I really need!

So have a Happy New year, and don't have nightmares...

Following a lovely Christmas with the newly-reconfigured family, nasty colds meant that many of us saw in the New Year with bugs that probably warrant their own X-file. I'm not a patient patient, and my cold was always much worse at night than during the day - leading to many a comparison between myself and one of the Gremlins (post midnight-snack.)

Being unwell on holidays really shouldn't be tolerated. In the same way the French protested against wheel clamping by injecting superglue into the lock of every contraption they happened across, Mother Nature should be forced to rethink; as each and any one of us shoves an Olbas inhalator up the nose of every passerby who sniffles within our reach.

My unseasonal malaise began just before Christmas, when I had to attend a routine check-up at the hospital. Due to a family history of Ulcerative Colitis (and a personal one come to that), I'm required to undergo cancer/abnormal-cell screening every couple of years. Now, it's never pleasant, but always necessary - and means letting a strange man get closer to me with a camera than even Paris Hilton would allow...

Honestly, people complain about CCTV, and "living in a Big Brother Orwellian State" but they haven't the faintest idea just how much of a liberty SnappySnaps and Co. actually take. Some things just ought not be captured on film; like any time Les Dennis or Keith Chegwin take their clothes off, or the inside of my remaining digestive tract. Colonoscopies are like clinical happy-slapping: inflicting pain on camera. Gregarious film critic Mark Kermode calls it "torture-porn" when they do so in movies, but I really don't think that what they do to me biannually is for anyone's gratification.

Ever since watching the BBC's season of charming Alan Bennett monologues, I can't help but read these more mundane of my ramblings in his distinctive kitchen-sink-drama voice. I have at least one acquaintance who finds Bennett inexorably dull, which probably lends itself better to the comparison than I have the right to seek in any other respect.

Due to a lack of inspiration - and indeed motivation - to write of late, I've found myself falling back in love with an old flame. What is the object of my re-ignited passion? ...Jewellery design.

Although as a dedicated logophile words will always be my first love, I must admit to several illicit affairs with various aspects of colour, shape and form. From a pre-pubescent love of photography, to an adolescent admiration for design, I have always enjoyed the creative process of weaving something that did not exist until I saw how it should be. All my writing stems from very similar origins, and my enjoyment of literary and fashionable pursuits have long jockeyed for position. Usually the two work reasonably well in tandem. I am flighty, and tire of projects easily, so when I become disillusioned with one outlet for my imagination, I've always been glad of the other to fall back on.

Writing is the one I could not live without - I'm far too opinionated and narcissistic not to have some journalistic outlet - but my eye for colour and unusual shapes means that design is very important to me too. It's a natural part of the way I interact with the world - I see it as an artist, albeit not one of any groundbreaking insight.

Professionally, there is very little opportunity to write at the moment, and apart from my usual poetic outlets, I've been lacking in productivity. Some poets can sit and write about any given subject 'on demand' - will themselves into a mindset where their talent is readily accessible. I, however, have never mastered that skill. While all creation - be it within science or the arts - is a somewhat magical affair, instead of being an alchemic recipe for new life and ideas, mine is far more of a New Age bastardization of Paganism. I don't mix all the ingredients and come up with something astonishing - I must just hang around on the second Tuesday of the full moon wearing red knickers, and wait for a word, or an idea to spark something into being. As the full moon this month was on a Wednesday and my red kecks were in the wash, no sparks flew. So back to jewellery design it is.

As the company I was involved with before have cut so many of its staff, I am not in the position I was previously of being able to design exquisitely expensive pieces and submit them to a workshop for manufacture. For a while at least, I will be back to making the items myself. Hopefully it will give me the chance to expand my silver and goldsmithing abilities, as I get back into manufacture as well as design. Gemmology is a subject I retain a highly-geeky knowledge of, and a return to jewellery design is an exciting prospect.

If and when I launch a few items online, it will be via an Etsy store, and I will announce the details and promotional codes here, so that those of you who suffer my ramblings have some form of compensation for so doing. So watch this space! ...Not literally. It could be a while, and if you just sit there watching then I'll end up being reported to Watchdog as the person responsible for your deaths - like the DJ who challenged his listeners to drink as much water as they could, and one of them died. While inciting such idiots to follow their natural instincts is not a crime I believe to be too heinous, nonetheless it's not the sort of publicity I really need!

So have a Happy New year, and don't have nightmares...

Sunday, 20 December 2009

0-800-Reluctant-Samaritan

I've neglected this blog for far too long, and there's no excuse for it really. Since I last plagued you with the contents of my slowly-scrambling brain, my father has married, and I managed not to make a fool of myself as a bridesmaid. Two more books have been printed, and the months since have flown past in a haze.

Before I have reconciled myself the the loss of the last Autumnal warmth, Christmas approaches. It looms less than a week away and I still have yet to do much shopping or write any cards. I'm going to buy a "Happy New Year" stamp and post them as soon as I get around to it. Everyone who lives further than the end of my street will not receive glad tidings until after the main event. Maybe I'll tell them I'm actually sending mine nearly a full year early, instead of being a few days late? Or I might say I've moved to Australia and write "hope this gets to you on time!" inside each card, so that people think I did my utmost to traverse the dense outback with the letters strapped to me, being dragged half the way to the post office by a semi-retired Skippy The Bush Kangaroo. Anything but the lackadaisical truth.

As I have spent the last few months lazily hibernating from the cold, little of consequence has happened in my world. The majority of my energy has gone into battling a chest infection that has seen my lungs look like I am spawning a new generation of Slimers for a Ghostbusters remake. I have continued to write, though not a great deal of it has been of anything resembling commercial quality.

Because I flatter myself that I am one of those onerously pretentious 'creative types' I always keep a notepad beside my bed, to try and jot down any poetry or design ideas I stumble upon in that woozy, otherworldly space between sleeping and waking. The spot where dreams meet reality is often a rich source of nonsense for me, but unfortunately it is seldom constructive. The latest page reads "eat breakfast" because if I have to be up early I will remember to do my makeup, but will forget to eat. Vanity over sustenance. I'm like that laboratory rat which pushes the pleasure button instead of the food one until it starves.

(Okay, at this juncture I googled "mouse makeup" looking for a cartoonish image to post here to break up the monotony of my rambling. Instead I found this photoshopped picture of a computer mouse that doubles as a cosmetic compact. And I want one.)

Occasionally, I will wake up with seemingly-coherent yet utterly-pointless notations scribbled and then signed, as if my egocentric subconscious thinks the notebooks will be discovered some time in the future, and wishes to ensure that my astonishing insights are correctly accredited. I encountered such self-inflicted ridiculousness a few nights ago, when – after washing biro off of my hands and wondering where it had come from – I remembered to check my notepad and found this scrawled there:

When you own a cat, you will – at some point – find yourself sitting on the toilet with the cat watching you from the cistern, promising to buy her a covered litter-tray for the bathroom if she will grant you some privacy in return."

It's things like that which make me glad that Big Brother is ending before I ever got desperate enough to appear on it. I'd get out of the house only to be locked up in somewhere more secure, that was monitored by more cameras...

Before I have reconciled myself the the loss of the last Autumnal warmth, Christmas approaches. It looms less than a week away and I still have yet to do much shopping or write any cards. I'm going to buy a "Happy New Year" stamp and post them as soon as I get around to it. Everyone who lives further than the end of my street will not receive glad tidings until after the main event. Maybe I'll tell them I'm actually sending mine nearly a full year early, instead of being a few days late? Or I might say I've moved to Australia and write "hope this gets to you on time!" inside each card, so that people think I did my utmost to traverse the dense outback with the letters strapped to me, being dragged half the way to the post office by a semi-retired Skippy The Bush Kangaroo. Anything but the lackadaisical truth.

As I have spent the last few months lazily hibernating from the cold, little of consequence has happened in my world. The majority of my energy has gone into battling a chest infection that has seen my lungs look like I am spawning a new generation of Slimers for a Ghostbusters remake. I have continued to write, though not a great deal of it has been of anything resembling commercial quality.

Because I flatter myself that I am one of those onerously pretentious 'creative types' I always keep a notepad beside my bed, to try and jot down any poetry or design ideas I stumble upon in that woozy, otherworldly space between sleeping and waking. The spot where dreams meet reality is often a rich source of nonsense for me, but unfortunately it is seldom constructive. The latest page reads "eat breakfast" because if I have to be up early I will remember to do my makeup, but will forget to eat. Vanity over sustenance. I'm like that laboratory rat which pushes the pleasure button instead of the food one until it starves.

(Okay, at this juncture I googled "mouse makeup" looking for a cartoonish image to post here to break up the monotony of my rambling. Instead I found this photoshopped picture of a computer mouse that doubles as a cosmetic compact. And I want one.)

Occasionally, I will wake up with seemingly-coherent yet utterly-pointless notations scribbled and then signed, as if my egocentric subconscious thinks the notebooks will be discovered some time in the future, and wishes to ensure that my astonishing insights are correctly accredited. I encountered such self-inflicted ridiculousness a few nights ago, when – after washing biro off of my hands and wondering where it had come from – I remembered to check my notepad and found this scrawled there:

When you own a cat, you will – at some point – find yourself sitting on the toilet with the cat watching you from the cistern, promising to buy her a covered litter-tray for the bathroom if she will grant you some privacy in return."

It's things like that which make me glad that Big Brother is ending before I ever got desperate enough to appear on it. I'd get out of the house only to be locked up in somewhere more secure, that was monitored by more cameras...

Sunday, 9 August 2009

A Matter of Life and Death

Well it finally happened, yes it finally happened. My sister's elephantine gestation came to an eventful end mid-morning on August 1st 2009, when she gave birth to a little girl called Chloe. I use the term "little" rather loosely, as when the child took her first breaths she was already of a size not dissimilar to that of most domestic cats. (Not our cat though. Even I struggle to match the size and weight of Tuppence.)

It was a particularly laboured labour, or at least felt like it, as my sister had convinced us all that the baby would be early, and by the time she actually arrived none of us were quite sure whether or not to believe it. "Well how much of the baby can you actually see? Because unless the feet are out there's still a chance she might climb back up again!" It is that attitude which saw me accused of not treating the arrival of my niece with due seriousness – but the honour of most-inappropriately-humorous approach goes to my stepmother-to-be, Sam. When Dad asked my sister's fiancée how things were progressing, he was told that the head was visible, and the baby appeared to have black hair. Now, did Sam respond with a saccharine comparison to Snow White's ebony tresses? No, she suggested that whilst it may be true that the crowning bonce may be furnished with dark locks, it was also equally possible that Sara just hadn't waxed in a while... (Suffice to say this alone gives me cause to have unwavering confidence in their impending nuptials. Anyone who feels comfortable enough to make that joke with their betrothed about his daughter – and in the process tickle him enough that he repeats it to his other daughter – has found their perfect match. ...Or will at least be doing mankind a favour by taking themselves off the streets.)

The day she was born I visited my niece in the hospital, and for once may not have been the most tired person in the room! Contrary to popularly exaggerated belief, I am adjusting to being an auntie. I still find it an appalling injustice that the universe is allowing my generation to breed, and think it is merely adding insult to injury that the baby is also ginger, but despite that I seem to be adapting. That is to say, adapting to the newfound knowledge that it is not actually necessary to take antihistamines before I go near baby Chloe, (though I am growing ever more convinced that there's no cure for the allergy I have to her mother.)

It was Chloe's irrepressible mother who last week announced that she was "absolutely certain" that I would not only marry but have a child of my own soon. The extent to which this has made everyone roar with laughter should be enough to tell you how unexpected a statement hers was. She was saying that when she marries it will be the end of the Lawrence line, as my father only had daughters and there is no one to carry the name into the next generation. I hastily reminded her that actually I've always said that I would double-barrel my surname (and that of any prospective progeny) for the very reason that being a Lawrence is far too important for me to discard. She replied "Oh, you know what I mean. Soon I'll be a Pollard, and you'll be whatever you're going to be in the near future." I nearly choked on my tea at that point, and she elaborated "Oh yes, I'm sure you'll get married soon. And me having Chloe will make you broody too. If I can do it so can you." Her manner was so offhand yet sure of itself that I was at a loss how to argue – save point out that irrespective of my many unfavourable thoughts on the subject, there are several practical steps missing before her prediction could be realised. My independence and lack of overt maternal instinct have meant that, generally, people do not ask me "when it's going to be [my] turn?" ...And if they do, they tend not to live very long.

A few people (all so blindly misguided that they need to sack their specially-trained Labrador,) have suggested that nursing Chloe should be making me broody. It isn't. Rightly or wrongly, she has as yet had no affect on my hormones, and I really don’t expect her to. That’s not to say that I’m without feeling when presented with a newborn; when next-door's cat had her kittens I wanted one so desperately that I explored every possible avenue via which I may at least retain contact with them. As my cat isn't very friendly, had the house been even a tiny bit bigger I would have considered sectioning my home into two halves; thereby keeping the kitten as my upstairs cat and allowing Tuppence to stay downstairs. (Any of you from the North, for whom "tuppence" shares a closser affinity with the word 'pussy' than it does with the word 'cat', may be sniggering right now. Stop it.)

When it comes to the human infant in my life, however, I feel very differently. I am not uncomfortable with her presence, and may even grow to like/love her as she develops a personality of her own – providing it differs greatly from that of her mother – but she does not ignite the desire to raise offspring of my own with any immediacy. The only life-event to have ever really focused my attention on reproducing, via anything other than cloning, was the death of my Grandfather: three years ago this week.