Friday, 23 May 2014

The Ties That Bind

Sometimes perspective is subtly gained, and other times it crashes into view and simply obliterates the previous mode of thinking. The hospital which has been its stage - and my home - for the last week is a master of shifting attitudes; an arena so cacophonous with extremes of emotion that few are seldom fixed.

Being quite experienced in pain and complexity, I've struggled much less with the physical reality of this current unwellness than I have with some of the wider questions it has thrown into my path. The now-unavoidable gastric surgery carries with it substantial risks to fertility, the extent of which I am only just beginning to explore with the help of relevant specialists from the field.

Suddenly finding myself asking very big questions about my future has been made particularly jarring because I had never given much thought to it before. My mother was in her late 30s when she became a parent, and even as a child I had always presumed that the same would be true of me. As ever greater numbers of my peers have begun to have families of their own, and the quantity of nieces and nephews I've amassed threatens to overwhelm the world supply of Jelly Tots, I still felt under no pressure to consider my own reproductive responsibilities. It was a question for another time, another decade. Something that seemed so abstract and far away, and felt almost ridiculous to ruminate upon seriously when it was so far from being relevant.

It is a theme repeated, I suppose, by couples everywhere who find themselves actually having to think about fertility. It's an aspect of our health we take for granted in a more absolute, evolutionary sense than we might any other, and do not test until it fails us. I had been as naive as anyone, never questioning my ability to have a child of my own, and indeed focused more on the rights and responsibilities afforded me not to get pregnant than anything else.

Much as I adore the cheeky, sticky, noisy, lovable riot of children to whom I am Auntie, I have been perfectly content to postpone any thought of adding to that brood myself. I'm not the type who coos and clucks over other people's babies, and don't have much experience entertaining children. This awkwardness led to a general assumption that I am not a very natural mother and a much more intuitive Wicked Queen. (It may also have something to do with the tiara, but I still deny responsibility for those poisoned apples.)

Despite the teasing, I don't think I had really given the concept of motherhood much thought at all until I was twenty. When my grandfather died it was earth-shattering, but somewhere amidst the shock and the grief and the pain was a strange kinship and familiarity. That moment of devastation linked me to the past in a way nothing could have done before. The loss of that great man and all that he was to us, and the staggering realisation that from that point on he could be only a memory, was when it all fell into place. I have referred to it since as my "circle of life moment", because I knew, there and then, that our lives have power and purpose simply because we share them. As I felt both the privilege and the loss of having been loved so much by someone I so admired, I recognised my place in the order of things in a way I had not done before. I wasn't just a daughter, or a granddaughter, I was a link in a chain that stretched back generation after generation, and - most startlingly - would reach out just as far into the future too.

I've touched on the significance of that moment before, but have found myself remembering it so much more acutely in the shadow of this latest news. As I indulged the self-pity and allowed myself to sink a little deeper into what was becoming quite a comfortable sulk, my whinge was interrupted by a whisper.

"Please let me go. Tell the children that I love them, but they must let me go."

An elderly lady in a bed across the ward is receiving only palliative care, and her lucidy drifts somwhere between remarkably keen and hopelessly lost, never certain which is cruellest. Tonight she has called alternately for her children, and her parents, earnestly seeking the comfort of those greatest loves as her life begins its end.

Her family is large and caring, guilty only in their eagerness to cherish the moments of respite from distress, despite - and because of - their rarity. It is impossible to watch life unfolding and untangling itself at such close hand without realising how small a part we each play. How insignificant the knots are in which we find ourselves tied, time and again, until there is no time. No "again". It isn't blood she calls to, or to which they cling, it's bond. A bond formed by loving as deeply, resolutely, and fearlessly as family demands, but which is not exclusive to genetics. It's the quality of the relationships that surround her which have brought the greatest joy to know, and are causing the most pain to leave, not their heritage.

As the spectre of their loss calls to the ghosts of mine, I find myself so very grateful for those in my life whom I would be most loathe to leave, family and friends, and equilibrium begins to restore. It's hard to be too dedicatedly self-pitying in the face of so much love, and life, and potential for more of the same. I may not know what shape my future will take, or how far it may deviate from the course I'd expected, but in this moment it is enough to possess the luxury of time to find out.

As the last of the ward lights are dimmed and the day's visitors reduced to a cluster of empty chairs, so she whimpers to the night and asks it to take her; eased of the pain her illness delivers but wracked with the agony she knows awaits them. She quietly asks the nurse if she can have something to cuddle, and they give her a pillow. As she falls asleep with it cradled tightly to her chest my heart breaks for far worthier tragedies than my own, but this single bed has never felt quite so vast.

Monday, 5 May 2014

Keep Kalms and Carry On

This blog began its life as a repository for all the nonsense burbling through my brain during a prolonged bout of insomnia. I've revisited it on occasion since, but never with the same committment. Some of that was because it became a victim of its own success; as more people confessed to having read it, the less about my life I could actually share for fear of upsetting or alienating those I am much fonder of than it might appear in print.

I find myself back here now not because I have anything more to say, but because I once again appreciate having a place to say it. Somewhere to unburden my mind of some of its turbulent tangle of thoughts and tangents. (Beginning with the excess of letter T's it seems.)

For the first time in a life that has grown steadily less ordinary, I've been unable to wend my way through that troublesome tangle of inner turmoil on my own. The blitz spirit indoctrinated by the grandparents who raised me failed in its robustness, and the moment came when I couldn't keep calm, and had no idea how to carry on.

That sounds terribly melodramatic but, momentarily, it was. I have long counseled others that we each have a point at which we break, but I had never expected to find mine. It's conceited of me, I suppose, to think myself immune to the stresses and psychological hardships that afflict others. I observed patterns of distress and depression in friends, family, and in my capacity as a peer counsellor. I have always believed that no one should be ashamed of asking for help, and that it is normal to feel overwhelmed sometimes. I offered support to others in the fullest sincerity of that belief, and have tried to learn from, and better comprehend, the processes involved with recovering and moving forward. As I write this, a University prospectus sits beside me with a page folded down to a counselling course I had hoped to pursue, while a leaflet for MIND volunteering opportunities is pinned to the noticeboard. I've championed the services available and actively sought to help others access them because I believe in the real, tangible value they offer to those who are struggling.

Yet, despite my vainly assured tolerance and experience, I not only failed to recognise the approach of my own crisis, but have reacted very reluctantly to the idea of treating it with medication and therapy. I have had to accept that not only am I human, but also a hypocrite. In a rather roundabout way, however, that admission may just be what gets me through it.

After fifteen years of ill health and disability, I first began to struggle when the prospect of further surgery was raised. I have, very fortunately, never been one to suffer from depression, but recall returning from hospital that day utterly exhausted and dejected. Defeated by a battle against my own body that I had thought was coming to an end. I lay in the garden as the disconcertingly beautiful sunshine slowly dimmed and the blaze dipped below the skyline. As I rested, I listened to Neil Gaiman's "Ocean At The End Of The Lane" audiobook, escaping into benign fantasy and letting the words swirl and cleanse as I railed against the bitterness and self-pity that kept trembling through my stiff-upper-lip. I will always be grateful to Gaiman for sending me a friend like Lettie when I needed her - almost as much as his ponderous protagonist did.

Over the following days I did what I always do, and 'got on with it'. Having been a sickly child I've come to be defined by the ability to cope. "She's a trouper!" "She's always so strong." "She never let's it get to her." How much of it I can claim was true I don't know, but it has become an important part of how I saw myself. It gave some sense of achievement and purpose to all the suffering I suppose, thinking that it was character building, and made the struggle less distressing for those around me who were helpless to improve my circumstances.

So as time moved on and other distractions presented themselves, I brushed the growing anxiety aside. It wasn't my way to indulge it, and I'm not sure I would even have known how to express it, or to whom. Then a spate of issues with uncertain consequences for my future left me feeling very anxious about the direction my life might take. I noticed it properly for the first time, like something moving from the corner of my eye into sharper focus. Yet still I dismissed the persistent, niggling, fear and busied myself with other things, and almost a year after the initial conversation about further surgery my consultant raised it as a much more immediate concern.

Suddenly I was forced to confront even more unsettling decisions about my future, including having to answer queries about my practical and emotional support networks, the stability of my relationship, and whether or not I wanted children. Contemplating the various alternate realities left me reeling and rudderless in an unforseen storm.

A series of fractures began to appear in the days preceding my first meeting with the surgeons, and instead of greeting the new challenges with the required patience and determination, I just...broke. The anxiety finally peaked, and the calamitous clash of thoughts and feelings that had been growing into a tight ball in my stomach welled up and out in incessant waves of anguish that I could neither hide nor prevent. I couldn't eat, or sleep. Couldn't stop crying, and was beset by a nervous shaking that would put Michael J Fox to shame. All the while the measured, logical voice in my head was curtly urging me to stop making such a fuss and pull myself together, but I failed to maintain my composure for more than a few minutes before the panic would take hold once more. Deciding whether I wanted toast or cereal felt like my whole life hinged upon the answer, which is entirely illogical for anyone who doesn't live in a low-budget, Serendipitous romantic comedy, or a medieval village plagued by ergotism.

Leaning heavily on the family whom I would usually endeavour to spare such distress, I ended up crawling into bed with my grandmother in the middle of the night, like a toddler hoping to shake off the monsters that have followed her out of a nightmare. I knew then that I had to give in and ask for the help I had so earnestly recommend to others. I made an appointment to speak to whichever doctor was on call and sat in the surgery fighting not to make a scene, lest anyone be more inconvenienced by my dismay than their own coughs, colds, or ingrowing toenails.

The young GP who eventually saw me was one of the few at our practice with whom I am not familiar. It relieved me greatly as it released me from feeling like I may be disappointing the others; those who had treated me for years and praised my fortitude for making all our lives that little bit easier.

She listened patiently as I explained what had brought me blubbering before her. I candidly confessed to the various triggers for my state - between profuse apologes for making such an abnormal fuss - and heard the reassurances it is usually my job to supply reflected gently back at me. I told her that my main objective was to regain some stability, as I had a lot of big decisions coming up - personally and medically - and needed to know that I was not letting them be governed by fear. She was far less surprised than I had been that the accumulative stress had reached an unmanageable peak, and recommended an antidepressant for the anxiety and counselling to try and better identify, and manage, its causes.

It has been a very odd experience, being suddenly so unfamiliar with myself, and one with which I am still coming to terms. A lot of time recouperating had previously allowed plenty of time for introspection, and as such I always felt quite satisfactorily attuned to my sense of the world and my responses to it. Now, taking pills to help dull the panic and awaiting a referral for therapy, I find myself overreacting to change and needing clear, stable plans and structures to avoid the lingering anxiety. It felt a little like going blind, in some respects. All of a sudden I could no longer rely on my brain to process information in the way it always had, and was left stumbling around in the dark trying to relearn how to function. How to interact with a world full of new obstacles that would have been much more easily negotiated before. (Blindness is probably far too extreme a parallel, but it was at least comparable to the helplessness of going on holiday and realising in the middle of the night that you need a wee and haven't got a torch.)

One of the driving factors in my resolution to pursue the prescribed counselling is the incredible strength in the face of adversity that has been demonstrated by those I myself have counseled. The people who bravely took the steps I directed them towards, despite being just as dogged by self-doubt, embarrassment, reticence, and reluctance as I am now. I owe it to them to practice what I preach, and perhaps owe it to myself to accept some of my own advice.

I want to better understand the process, and understand this new, fractured facet of myself better too. So I'll start by being more honest with the people around me for whom I have maintained the expected facade. Now that the tablets are kicking in and I have begun to regain a much healthier perspective, it is easy to pretend everything is fine simply because I'm uncomfortable with making a fuss about the fact that it isn't. I know I need to work on not viewing my own vulnerability as weakness, and trust the people closest to me to be strong enough to cope with the truth, even if it isn't pretty. Life will continue to present difficulties, and test the limits of my tolerance, but I believe absolutely - as I did even at my lowest - that things will improve. This will pass, and I will be "ok". As I take the first steps towards being truly, positively, content again, I'm very grateful to be so certain that it shall come to pass. I know how many others have to find a way through their darkest nights without the certainty that they will soon feel the warmth of the day. It is for those people whom I write this and offer some company in the darkness, as they find a way back to the light. (As long as none of them piss in the wardrobe again.)

Thursday, 1 March 2012

Caller ID

Today was the 1st of March, and the welcome sunshine heralded the forthcoming spring. There was a freshness to the world, promising to breathe the colour and life back into all those too-long warmed by radiators and thermal socks. The trees have begun to bud, daffodils have started pushing golden trumpets skyward through the slowly thawing ground, and birdsong’s returning to hedgerows as the hardy winter species take advantage of insects enlivened by the unexpected sun. It was a day of beginnings.

Once home, as buoyed by the fresh air and sense of optimism as any good cliché expects, I smiled at the shrill ring of the house-phone and made sure to grab the mug of freshly-brewed tea on-route to answer. There are only a few who’d call the landline at that time of day, and I assumed it would be my friend Chris, wanting to catch up after a few weeks of radio silence from us both. A good cuppa and comfortable seat are a necessity when such a lengthy chat’s anticipated, and as I picked up the receiver and settled down with both, I’ll admit to being unprepared for the female voice on the other end. As soon as she introduced herself as his mother, I knew I wouldn’t touch the tea.

Chris and I met seven years ago through his wife, Elaine, when we found ourselves thrown together on a hospital ward full of elderly ladies. We shared a sense of humour, and quickly formed a friendship forged through long days spent in opposite beds, with little else to entertain us but each other. On her way back through the foyer having been out for a cigarette, she’d passed the charity stall and bought me a squishy little elephant that was full of beans. Someone had told her many years ago that because elephants never forget, if you give someone an elephant, it means they’ll never forget you. We laughed about it and stood it on the windowsill with a little grey cat visiting family had brought her, and which she’d named after me. One day after a trip out on “day release” I returned so tired that I could do little more than curl up on the bed fully dressed. Without a word she padded over and unbuckled my shoes, doing the only thing she could think of to make me a little bit more comfortable, hoping I’d relax enough to sleep despite the increased pain and nausea that I’d been admitted for in the first place.

Elaine's gift.

We were all surprised when her condition deteriorated overnight, and though she clung to life for a few more days, when I saw her in the private room she’d been moved into there was little left of the vibrant, giggling woman I’d bonded with on the ward. Her husband kept in touch because he thought it was what she would have wanted, and over the years we became friends.

Although my only contact with Chris has been through regular phone-calls, he’s always been interested in what I’ve been up to, and always cared very much that I remain healthy and happy. His career in the forces left him with scars deeper than those which had previously hospitalised me, and occasionally he’d recount some of the nightmares which had outlasted his service. Those tales weren’t always easy to hear, but were tempered with anecdotes about his time in Germany, the antics of the five cats he’d raised from kittens, and his enduring passion for science and astronomy.

Several attempts have been made throughout the years, by me and by his friends and family, to dissuade him from drinking as heavily as he began to following Elaine’s death. But he never slept soundly without her, and couldn’t imagine spending his life with anyone else. Until today I’d never spoken to his mother directly, simply heard him speak of her, often mentioning how robust she was for a woman of eighty who had still cared for her own mother until recently. I can’t count the number of times Chris joked about the longevity in his family, and talked about outliving me despite being thirty years my senior. Thirty years to the day, as the same date in April birthed us both, and made the annual well-wishes much easier to remember!

As the very last of the sun streamed through the window, warming the seat I’d curled up in to chat with him, his mother quietly explained how her son had been found dead. It was a strangely civilised and emotionless call; her supplying the details, me offering the condolences, us both agreeing that the news wasn’t entirely unexpected. I felt sorrier for her than for him in many ways, because he’d been very philosophical about his lack of desire to live without Elaine. He’d lost a life he no longer wanted, but she’d lost a son she’d never given up hope would learn to cope on his own. The tears that followed the click of the receiver flowed for so many things. The shock of the news after expecting his cheery refrain to greet me, the familiarity of the hurt I knew his family would be feeling, and the uncompromising contrast between the afternoon’s positivity and the sadness that was creeping in with the evening shade.

Long ago I’d had to accept that I couldn’t “fix” Chris. That none of the people who cared for him could do that. The best I could offer was to be his “little friend,” as he always referred to me, mainly to wind me up. I listened to him, laughed with him, and let him cry when he needed to. In return he cared, and repeatedly reassured me that he’d always be there if I needed him. Despite his flaws and failings, and all the people he had let down over the years – including himself – he really meant it. In a funny sort of way I always knew I could rely on him. He was determined to do right by me because of Elaine, and never went very long without giving me a ring to check that all was right with my world.

The only wobble during today’s call came when his mother asked me if she could phone me from time to time, to keep in touch, because she thought it would be what Chris would have wanted. I assured her that she was welcome to ring at any time, and I was always here if there was anything she needed. I’ll do my best to listen. I’m sure we’ll laugh sometimes. And I’m sure there will be times she’ll need to cry.

The weather report for tomorrow says it’s turning colder. Spring isn’t beginning yet after all. First, winter must end.

Once home, as buoyed by the fresh air and sense of optimism as any good cliché expects, I smiled at the shrill ring of the house-phone and made sure to grab the mug of freshly-brewed tea on-route to answer. There are only a few who’d call the landline at that time of day, and I assumed it would be my friend Chris, wanting to catch up after a few weeks of radio silence from us both. A good cuppa and comfortable seat are a necessity when such a lengthy chat’s anticipated, and as I picked up the receiver and settled down with both, I’ll admit to being unprepared for the female voice on the other end. As soon as she introduced herself as his mother, I knew I wouldn’t touch the tea.

Chris and I met seven years ago through his wife, Elaine, when we found ourselves thrown together on a hospital ward full of elderly ladies. We shared a sense of humour, and quickly formed a friendship forged through long days spent in opposite beds, with little else to entertain us but each other. On her way back through the foyer having been out for a cigarette, she’d passed the charity stall and bought me a squishy little elephant that was full of beans. Someone had told her many years ago that because elephants never forget, if you give someone an elephant, it means they’ll never forget you. We laughed about it and stood it on the windowsill with a little grey cat visiting family had brought her, and which she’d named after me. One day after a trip out on “day release” I returned so tired that I could do little more than curl up on the bed fully dressed. Without a word she padded over and unbuckled my shoes, doing the only thing she could think of to make me a little bit more comfortable, hoping I’d relax enough to sleep despite the increased pain and nausea that I’d been admitted for in the first place.

Elaine's gift.

We were all surprised when her condition deteriorated overnight, and though she clung to life for a few more days, when I saw her in the private room she’d been moved into there was little left of the vibrant, giggling woman I’d bonded with on the ward. Her husband kept in touch because he thought it was what she would have wanted, and over the years we became friends.

Although my only contact with Chris has been through regular phone-calls, he’s always been interested in what I’ve been up to, and always cared very much that I remain healthy and happy. His career in the forces left him with scars deeper than those which had previously hospitalised me, and occasionally he’d recount some of the nightmares which had outlasted his service. Those tales weren’t always easy to hear, but were tempered with anecdotes about his time in Germany, the antics of the five cats he’d raised from kittens, and his enduring passion for science and astronomy.

Several attempts have been made throughout the years, by me and by his friends and family, to dissuade him from drinking as heavily as he began to following Elaine’s death. But he never slept soundly without her, and couldn’t imagine spending his life with anyone else. Until today I’d never spoken to his mother directly, simply heard him speak of her, often mentioning how robust she was for a woman of eighty who had still cared for her own mother until recently. I can’t count the number of times Chris joked about the longevity in his family, and talked about outliving me despite being thirty years my senior. Thirty years to the day, as the same date in April birthed us both, and made the annual well-wishes much easier to remember!

As the very last of the sun streamed through the window, warming the seat I’d curled up in to chat with him, his mother quietly explained how her son had been found dead. It was a strangely civilised and emotionless call; her supplying the details, me offering the condolences, us both agreeing that the news wasn’t entirely unexpected. I felt sorrier for her than for him in many ways, because he’d been very philosophical about his lack of desire to live without Elaine. He’d lost a life he no longer wanted, but she’d lost a son she’d never given up hope would learn to cope on his own. The tears that followed the click of the receiver flowed for so many things. The shock of the news after expecting his cheery refrain to greet me, the familiarity of the hurt I knew his family would be feeling, and the uncompromising contrast between the afternoon’s positivity and the sadness that was creeping in with the evening shade.

Long ago I’d had to accept that I couldn’t “fix” Chris. That none of the people who cared for him could do that. The best I could offer was to be his “little friend,” as he always referred to me, mainly to wind me up. I listened to him, laughed with him, and let him cry when he needed to. In return he cared, and repeatedly reassured me that he’d always be there if I needed him. Despite his flaws and failings, and all the people he had let down over the years – including himself – he really meant it. In a funny sort of way I always knew I could rely on him. He was determined to do right by me because of Elaine, and never went very long without giving me a ring to check that all was right with my world.

The only wobble during today’s call came when his mother asked me if she could phone me from time to time, to keep in touch, because she thought it would be what Chris would have wanted. I assured her that she was welcome to ring at any time, and I was always here if there was anything she needed. I’ll do my best to listen. I’m sure we’ll laugh sometimes. And I’m sure there will be times she’ll need to cry.

The weather report for tomorrow says it’s turning colder. Spring isn’t beginning yet after all. First, winter must end.

Wednesday, 22 February 2012

Conversation with a Spamwhore

I have neglected this blog since I started getting the insomnia under control, but was reminded of it tonight when I received the most convoluted unsolicited email I've had since somebody passed my details on to the Nigerian royal family. And genereous as they were, boy were they difficult to shake off! I told them I couldn't handle the responsibility of millions of pounds being transferred into my bank account, but I guess people raised in privilege will never understand my life. When I wish that I could win the lottery, I always work out what the minimum would be that myself and my family/friends would need to live comfortably, and hope for that. If I had too much money I'd probably spend it on shoes. ...Well, shoes and every Big Issue seller with a dog. I'll sometimes walk past a Big Issue seller if all they have is a risk of pneumonia, heartwrenching sadness emanating from their person, and a distinct case of malnutrition. But if they have a dog, I crumble. If they're keeping it warm inside their coat, there's every chance I'll hand over the keys to my house and move into the shed.

This email failed to appeal to that conscience, warped as it is. In fact, it may not even be worthy of the derision contained within this post. I should have just deleted it and moved on with my life. But because I was bored I wanted to feel like I was doing something more constructive than daydreaming about not winning the lottery. So the correspondence is faithfully reproduced here (though fragmented for comic effect) with my thoughts as it progressed toward its agenda.

____________________________________________

"BABE... i guess your not getting any of my email huh? ive been

tryign to email u so many times but this dam laptop is such a piece of

garbage and keeps freezing.."

HI! No, this is the first email. My laptop can be a bitch too. So... who is this?

"anyways how u been? In case u dont know

who this is its ME ADRIANA.."

Who?

"we used to chat a bit on facebook and then

I think u deleted me :( "

Probably for repeatedly abbreviating the word "you".

"haha.. anyways guess what... I got 2 things to

tell u.. both good news.."

You're getting sterilised and joining a silent order?

"1) im single now.. yup me and my bf broke up

about 3 months ago..."

Don't tell me, he found out that you're actually the age suggested by your reading level?

"and 2) guess where im moving? RIGHT EFFING NEAR U.."

NO EFFING WAY!

"lol... ur actually the only person im gonna know there.. well 3

cousins too but i cant chill with them"

Why is it awkward, are two of them unhappy that you're marrying the 3rd?

"lol..I remember when we chatted u told me u thought i was cute and u wanted to chill so now we finally can"

That doesnt sound like me.

"HAHA! im kinda scared to move.. im hoping this email addy is still the one you use and u can chat with me ebfore i get there.. maybe even help me move my shit in...are u still on facebook? i cudnt find ui was soo confused"

That means I blocked you. And your shit.

"...anyways im gonna need someone to show me the town and take me out so u better be around bebe...we only chatted a couple times but i remember thinking to myself i wanted to get ot know u better when i was single..a nd i thoguth u were cute too but cudnt tell u cause i wasnt single lol..."

You're not the weirdest person to have called me cute this week, but he's still more my type than you are.

"ok so more info about me.."

I think I know everything I need to already.

"well im 23.. virgo.. love the outdoors and love to socialize, go out for drinks, restaurants, movies etc.. travel.. "

Maybe I shouldn't judge a book by its crayola-scrawled cover. You really don't sound that bad.

"i have a lil kitty named BOO and i luv her to death... "

I take that back.

"uhhh oh im a super horny gurl too but every gurl is they just wont admit it."

That's more information about you than I need. I can't vouch for the legitimacy of your generalisation, either, as I'm not familiar with the supposed reticence of "gurls". Women, on the other hand, are far more candid about our needs than you seem to appreciate.

"so ilove watching p0rn and all that.. love sex etc blah blah blah...who doesnt.."

You actually seem rather blase. I'm not convinced you enjoy it very much at all. Maybe breaking up with your boyfriend was for the best. He can't have been very good.

"I really hope we get a chance to chat for a bit either online or on the fone before i get there enxt week."

If you think I've deleted and blocked you on facebook, what do you think the chances are that I'll answer your calls?

"OH YA also.. i need to find a job when i get there.. do u have any hookups or know anybody hiring? id LOVE to work in a bar or osmehting like that...really anythgin cause my current job is fun and all.. and technically i CUD keep doign it but i want a change.. i currently work from home and well thats cool but i need ot be out meeting people.."

The person you have me confused with must work for the Jobcentre. I can see why they've been ignoring you.

"oh wait. i dont think i ever actually told u what i

did? hmm shud i......????"

Not unless you work for the Samaritans, because I'm already losing the will to live.

"ok WELLLL... and dont get all weirded out on me.."

I'm chatting to an email, you'd be surprised what I consider sane.

"i work on a webcam chat community site and i get paid to chat with people and get naked HHAHA... BOMB right :)? I KNOW.. like i figure iim horny anyways why not get paid to chat with people and play with myself heheh...anyways i hope u dont look down on that"

Not as much as I look down on your grammar. If you're recruiting, then ask me again if we hit a secondary recession.

"NO THATS NOT WHY IM CONTACTING U RELAX URSELF"

Well geez, I'm no supermodel but there's no need to be quite so sure.

"lol... i actually need help once i move and i remembered u live there so im reaching out....like i said before this computer is a complete piece of CRAP and freezes NON STOP.. ive tried ot send this email to u maybe 3 times already and im hopign this time i can hit SEND before i run into trouble lol.."

I don't see how I can help. I've neither a van nor a qualification in IT maintenance.

"ANYWAYS.. heres the deal....every month natalie (my boss) gives each of us 3 VIP codes to give out to whoever we want.. so with this code u can lgoin to watch me at work for free and dont have to pay like everyone else..."

Good for Natalie. I'm sure that will help you break the ice with your trio of cousins.

"i figured u cud always email me back instead but my email account doesnt even let me login half the time.. so the bets palce ot chat me is my chat room..."

It sounds like it'd be the worst place to chat with you. You type awfully as it is, I dread to think what state your penmanship (or keyboard) would take if you were engaged in your work, and I'd prefer not to fraternise with your clients.

"so the bets palce ot chat me is my chat room... if theres anyone else logged in when u sign in ill boot them out.. but remember DONT SHARE THIS PASSWORD PLEASE BABE IM BEGGING U.. I TRUST U... "

Can't you just give me a number, then I can confirm that I'm not who you think I am without opening my laptop up to the viruses and malware that are making yours so buggy?

"im online most of the day now to try and save money for my move..

also since im in such a huge debt already form my student loan :("

Media Studies or beauty therapy?

"I really thingk we need to chat before i get there and make sure u evern remember me hahha.. anyways ive rambled on and on now and ur probably soooo annnoyed with me so ill stop now.. im gonna go start work.. i really hope u come chat me. it wud make my day and releive a lot of my stress about the move... REALLY i mean that"

I have no recollection of you at all, and would discourage you from moving. Especially if it's closer to me. Relieve all the stress by staying put.

"once i see u in insdie ill shoot u myc ell number and u can gimme yours.. if u dont wanna come chat i understand but its really the only palce to find me now days.."

Just email your number, then you needn't deprive one of your future uncle-husbands of their VIP pass.

"hahahahha...k babe im out for now... chat ya soon..."

I really hope not.

____________________________________________

Anyone looking for the link contained within the original email should click here

This email failed to appeal to that conscience, warped as it is. In fact, it may not even be worthy of the derision contained within this post. I should have just deleted it and moved on with my life. But because I was bored I wanted to feel like I was doing something more constructive than daydreaming about not winning the lottery. So the correspondence is faithfully reproduced here (though fragmented for comic effect) with my thoughts as it progressed toward its agenda.

____________________________________________

"BABE... i guess your not getting any of my email huh? ive been

tryign to email u so many times but this dam laptop is such a piece of

garbage and keeps freezing.."

HI! No, this is the first email. My laptop can be a bitch too. So... who is this?

"anyways how u been? In case u dont know

who this is its ME ADRIANA.."

Who?

"we used to chat a bit on facebook and then

I think u deleted me :( "

Probably for repeatedly abbreviating the word "you".

"haha.. anyways guess what... I got 2 things to

tell u.. both good news.."

You're getting sterilised and joining a silent order?

"1) im single now.. yup me and my bf broke up

about 3 months ago..."

Don't tell me, he found out that you're actually the age suggested by your reading level?

"and 2) guess where im moving? RIGHT EFFING NEAR U.."

NO EFFING WAY!

"lol... ur actually the only person im gonna know there.. well 3

cousins too but i cant chill with them"

Why is it awkward, are two of them unhappy that you're marrying the 3rd?

"lol..I remember when we chatted u told me u thought i was cute and u wanted to chill so now we finally can"

That doesnt sound like me.

"HAHA! im kinda scared to move.. im hoping this email addy is still the one you use and u can chat with me ebfore i get there.. maybe even help me move my shit in...are u still on facebook? i cudnt find ui was soo confused"

That means I blocked you. And your shit.

"...anyways im gonna need someone to show me the town and take me out so u better be around bebe...we only chatted a couple times but i remember thinking to myself i wanted to get ot know u better when i was single..a nd i thoguth u were cute too but cudnt tell u cause i wasnt single lol..."

You're not the weirdest person to have called me cute this week, but he's still more my type than you are.

"ok so more info about me.."

I think I know everything I need to already.

"well im 23.. virgo.. love the outdoors and love to socialize, go out for drinks, restaurants, movies etc.. travel.. "

Maybe I shouldn't judge a book by its crayola-scrawled cover. You really don't sound that bad.

"i have a lil kitty named BOO and i luv her to death... "

I take that back.

"uhhh oh im a super horny gurl too but every gurl is they just wont admit it."

That's more information about you than I need. I can't vouch for the legitimacy of your generalisation, either, as I'm not familiar with the supposed reticence of "gurls". Women, on the other hand, are far more candid about our needs than you seem to appreciate.

"so ilove watching p0rn and all that.. love sex etc blah blah blah...who doesnt.."

You actually seem rather blase. I'm not convinced you enjoy it very much at all. Maybe breaking up with your boyfriend was for the best. He can't have been very good.

"I really hope we get a chance to chat for a bit either online or on the fone before i get there enxt week."

If you think I've deleted and blocked you on facebook, what do you think the chances are that I'll answer your calls?

"OH YA also.. i need to find a job when i get there.. do u have any hookups or know anybody hiring? id LOVE to work in a bar or osmehting like that...really anythgin cause my current job is fun and all.. and technically i CUD keep doign it but i want a change.. i currently work from home and well thats cool but i need ot be out meeting people.."

The person you have me confused with must work for the Jobcentre. I can see why they've been ignoring you.

"oh wait. i dont think i ever actually told u what i

did? hmm shud i......????"

Not unless you work for the Samaritans, because I'm already losing the will to live.

"ok WELLLL... and dont get all weirded out on me.."

I'm chatting to an email, you'd be surprised what I consider sane.

"i work on a webcam chat community site and i get paid to chat with people and get naked HHAHA... BOMB right :)? I KNOW.. like i figure iim horny anyways why not get paid to chat with people and play with myself heheh...anyways i hope u dont look down on that"

Not as much as I look down on your grammar. If you're recruiting, then ask me again if we hit a secondary recession.

"NO THATS NOT WHY IM CONTACTING U RELAX URSELF"

Well geez, I'm no supermodel but there's no need to be quite so sure.

"lol... i actually need help once i move and i remembered u live there so im reaching out....like i said before this computer is a complete piece of CRAP and freezes NON STOP.. ive tried ot send this email to u maybe 3 times already and im hopign this time i can hit SEND before i run into trouble lol.."

I don't see how I can help. I've neither a van nor a qualification in IT maintenance.

"ANYWAYS.. heres the deal....every month natalie (my boss) gives each of us 3 VIP codes to give out to whoever we want.. so with this code u can lgoin to watch me at work for free and dont have to pay like everyone else..."

Good for Natalie. I'm sure that will help you break the ice with your trio of cousins.

"i figured u cud always email me back instead but my email account doesnt even let me login half the time.. so the bets palce ot chat me is my chat room..."

It sounds like it'd be the worst place to chat with you. You type awfully as it is, I dread to think what state your penmanship (or keyboard) would take if you were engaged in your work, and I'd prefer not to fraternise with your clients.

"so the bets palce ot chat me is my chat room... if theres anyone else logged in when u sign in ill boot them out.. but remember DONT SHARE THIS PASSWORD PLEASE BABE IM BEGGING U.. I TRUST U... "

Can't you just give me a number, then I can confirm that I'm not who you think I am without opening my laptop up to the viruses and malware that are making yours so buggy?

"im online most of the day now to try and save money for my move..

also since im in such a huge debt already form my student loan :("

Media Studies or beauty therapy?

"I really thingk we need to chat before i get there and make sure u evern remember me hahha.. anyways ive rambled on and on now and ur probably soooo annnoyed with me so ill stop now.. im gonna go start work.. i really hope u come chat me. it wud make my day and releive a lot of my stress about the move... REALLY i mean that"

I have no recollection of you at all, and would discourage you from moving. Especially if it's closer to me. Relieve all the stress by staying put.

"once i see u in insdie ill shoot u myc ell number and u can gimme yours.. if u dont wanna come chat i understand but its really the only palce to find me now days.."

Just email your number, then you needn't deprive one of your future uncle-husbands of their VIP pass.

"hahahahha...k babe im out for now... chat ya soon..."

I really hope not.

____________________________________________

Anyone looking for the link contained within the original email should click here

Monday, 27 December 2010

And Now For Something Completely Different

As I am the only one of my siblings who has (happily) not yet begun breeding, this Christmas the family was scattered around visiting other children and grand-children – with a smaller local gathering planned for New Year. Like many people, I’m not very keen on change when it is thrust upon me, and am particularly averse to it when it involves traditions which I enjoy the comforting familiarity of. I’m still vaguely traumatised by Katie Melua replacing Kirsty McColl on the Pogues re-released ‘Fairytale of New York’ a couple of years ago, so knew that I may very well be uncomfortable with the idea of not spending Christmas day with my close family after almost a quarter of a century of doing just that. As with any variation on a classic, this re-mixed Christmas was always going to feel a little odd – but rather than sulking or resisting the change, I thought that I would use the opportunity to do something completely different.

I’ve long wanted to be more involved in community volunteering, and thought that this quiet Christmas might provide the perfect opportunity to exercise my atrophied humanitarian muscles. It’s not easy to be a slightly misanthropic humanitarian, but it’s a similar inner-conflict to being a cynical idealist, so is a contrary state of being which I have learnt to accept. In late October I began emailing local charities and organizations who I thought might be working with disadvantaged members of the community this Christmas-time. Restricted slightly by the limited public transport and the fact that I don’t drive, I took a chance on contacting the church that sits at the top of my street. It’s been here longer than I have, but the last time I was inside it I can’t have been much more than about 7 years old. A friend of the family had invited me to a Sunday School program which had been set up during the summer holidays, and I went along because someone said that all the stories were told with puppets, and that all the hymns usually reserved for school assemblies would be accompanied by guitar. (I had a very sheltered childhood and that seemed intriguingly novel.) At the time it seemed fun and friendly, but I didn’t go to more than a couple because I felt very out of place. I shouldn’t have, as I knew several of the other children there and I was familiar with the fables and bible stories being so cheerfully narrated, but even then I just didn’t feel like my faith fit their formula. I very much enjoyed Religious Studies at school, but didn’t ever feel compelled to sign up to any of the religions we covered. I liked bits from them all, and for me that was good enough. In many ways it still is, though I put more faith in science and people than I do much else. That said, I still have room in my life for some spirituality, and like the “safety net” of thinking that there is something out there in case I screw up. I don’t need to analyse it or explain it, and don’t feel the need to probe it further. People of faith often have some difficulty with this, because they want me to commit to one or other god/religion, and seek to categorise or convert my non-specific ‘hope’ into a tried-and-tested ‘belief’.

Partly because of this unsuitability, I had mixed feelings when the church got back to me at the end of November with a list of seasonal suggestions for helping out over the holidays. The opportunity they offered was perfect in so many ways; so local it was within spitting distance of the house, on Boxing Day so that I didn’t have to leave my grandmother alone at Christmas, and it was an event for lonely and disadvantaged residents (which, due to my Social Worker gene, pleased me more than the convenience). I was apprehensive though, because I remembered how out of place I had always felt there – and was fully aware that I hadn’t set a stiletto’d foot inside a church for more than a wedding, christening, funeral or carol concert in nearly a decade. The event they had organised was a Christmas service with carols, followed by coffee, a buffet lunch, and then an afternoon of entertainment, and was open to anyone with nowhere else to go; asylum seekers, the homeless, immigrants, singles, vulnerable people, and the elderly.

When arranging to help I had politely opted out of the morning service, and arrived later to prepare lunch and set the tables. The church has undergone major redevelopment recently, and is still only half-finished. I’ll admit to feeling a little overwhelmed by the now-unfamiliar building, and the sea of equally-unfamiliar faces whose accompanying names I’d forgotten almost before I’d finished shaking their hands. Putting my discomfort and the redundant introductions aside, I busied myself with the tasks set by the Leader of the Kitchen People. It was obvious immediately that the warm and approachable women in charge of today’s buffet had limited experience catering for charity. I grew up helping with the New Year’s Eve buffet at the Community Centre my grandfather ran, and helped with it almost every year from early childhood until his death when I was 19. Whether it was gathering balloons, buttering bread or – my very earliest job putting hundreds of sausages on sticks – I’d participated in a lot of buffet-cooking on a budget. These ladies, though all very nice, obviously had not. The food was lovely, but the presence of a pack of luxury Organic Jersey butter meant that their inexperience of low-cost cuisine was rather telling.

Within minutes of my arrival I was slicing baguettes for the garlic bread, and it became apparent that the ovens were no longer working. (It became apparent because the electricity for the whole room shorted.) Wondering how there could be a smell of burning when the oven was out, it was soon discovered that the smoke was coming from the electrical socket the oven had been plugged into. Due to the building work, the electrical supply to the points in the kitchen hadn’t been connected, so the Leader of the Kitchen People had plugged it into a 13amp socket on a reel of the builder’s extension cables. This shouldn’t have been amusing, but a long-standing joke between friends and me has been that none of us are saintly enough for churchgoing, and would probably be struck by lightning if we ever entered one at all. As I was stood a couple of feet at most from the oven and power-socket when it burst into flames, a little corner of my smoke-blackened soul wanted to jeer a triumphant “Ha! You missed!” in the direction of the church hall. More appropriately, I suggested that we take the trays of half-cooked food down the street to finish them off in my home oven, because the alternative was to serve little other than crusty bread and cherry tomatoes.

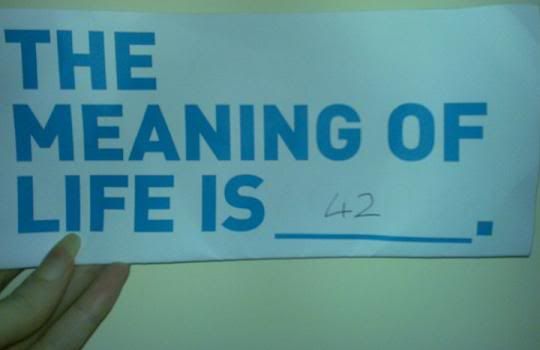

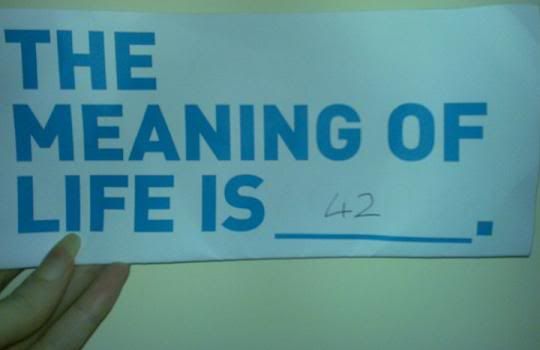

With lunch rescued and tables set, it was time to mingle with some of the event attendees, who were a very mixed – but over-all very lovely – bunch of people from all kinds of backgrounds. After coffee it was time for people to sit down to lunch. After my first gaffe – continuing to set Christmas crackers on the tables while they were saying grace, until I realised I should step back and stand still – lunch went pretty smoothly. Everyone was fed, and chatting to some of the other volunteers was nice. After setting out the food and making tea, I found myself seated between a particularly friendly couple who lived and worked locally and who were both fun, lively company, and a sweet Zimbabwean lady who had no family in the country. It was when chatting with the volunteers and other ‘regulars’ that I encountered the only nagging awkwardness of the day, which came every time anyone asked me which church I worship at, or asked how long I had been coming to theirs. Quietly saying that I am not a churchgoer and was just helping out seemed to satisfy some, and they were additionally thankful that I had spared my time for complete strangers. Others wanted a little more detail, and continued to advocate their different services to try and persuade me to join them. None were too pushy once I aired my Agnostic card, which I was pleased about. I had hoped to overturn the unfortunate stereotype all too commonly encountered in other religious folk, which involved any attempt to convert me, but was unfortunately unsuccessful. There was only one particularly dogged attempt to get me to come along to their services, but I think it backfired a little. I’d noticed a little leaflet placed on the table near me when she returned from fixing herself a coffee, but my only temptation to look at it came from the overwhelming desire to graffiti it. The leaflet had “The meaning of life is ____.” printed onto it in bold blue letters, and had I not been surrounded by disapproving people then I would have succumbed to the impulse to scrawl “42” in the blank space, a la Douglas Adams’ answer to the ultimate question in Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. While they were watching the film, I was sneaking a photo of the leaflet to announce my compulsion via Facebook as a way of preventing myself from fulfilling it in plain sight of the congregating Christians.

Not long after this, I was given the leaflet and told that it detailed an educational program designed to “explain Christianity”. She then asked me what I knew about the Alpha Course. Well, this presented the second point of awkwardness, because the only thing I really know about the Alpha Course comes from articles and documentaries by Jon Ronson, where he exposes the emotional manipulation behind the charismatic and persuasive approach, which at its zenith encourages speaking in tongues. I think she realised that I was unlikely to follow it up at that point, but I took the leaflet because I’d spent two hours wanting to do this:

A short clip where Ronson provides a brief but suitably sceptical description of the Alpha Course:

The entertainment for the day turned out to be not all that different to my Sunday School experience, as in the very same hall after lunch a man sat down with a an acoustic guitar, and vainly attempted to get people to sing along, before letting them play games instead. The only difference now was that instead of snakes and ladders they brought out a Nintendo Wii, which one of the younger volunteers attempted to teach a couple of old ladies how to play. The games were gradually replaced with quieter pursuits, as a handful of people settled into a game of scrabble, and everyone else relaxed into comfy chairs to watch a movie. Since puppets had been pivotal to my previous encounter, I was amused that the film chosen was Muppet Christmas Carol, bringing them to the fore once again.

Most people go to church to find God; whenever I go I find Jim Henson.

One older lady who was either Jamaican or Ghanaian giggled solidly throughout the movie, muttering to herself throughout the plot and gripping my arm while bent-double with laughter whenever any of the mice or Rizzo the Rat came on-screen. When it was over she asked if “the local library would have the book the film was made from” and asked who it was by. Considering that there is a Charles Dickens museum in Portsmouth, which faithfully recreates and preserves the house he was born in, it is uncommon to come across anyone who doesn’t know at least a little about the man. Dickens is such a traditional and iconic part of our local and national literary heritage that it was odd, for a moment, to find someone who was discovering him and his most famous Christmas tale for the first time. It was also lovely, because all the magic and laughter and emotion which I associate with my own childhood memories of the film was present in her experience of it, which was charming in its purity. She was thrilled with every scene, and completely wrapped up in the colourful cast of characters. It was a delight to witness, knowing as we explained Dickens to her that there was such a wealth of literature for her to explore next. Though if she’s hoping for a version of Great Expectations featuring Kermit as Pip and Miss Piggy as Estella, then I fear that she will serve only to confuse the librarian.

It was a very nice day on the whole, which succeeded in changing my Christmas routine enough that it was not only fulfilling, but far less strange. Before today my impressions of the local church had been limited to guitar music, puppetry, people trying to convert me, and a fear of catching fire. Now? Well… I’ll always associate it with sausage rolls too.

I’ve long wanted to be more involved in community volunteering, and thought that this quiet Christmas might provide the perfect opportunity to exercise my atrophied humanitarian muscles. It’s not easy to be a slightly misanthropic humanitarian, but it’s a similar inner-conflict to being a cynical idealist, so is a contrary state of being which I have learnt to accept. In late October I began emailing local charities and organizations who I thought might be working with disadvantaged members of the community this Christmas-time. Restricted slightly by the limited public transport and the fact that I don’t drive, I took a chance on contacting the church that sits at the top of my street. It’s been here longer than I have, but the last time I was inside it I can’t have been much more than about 7 years old. A friend of the family had invited me to a Sunday School program which had been set up during the summer holidays, and I went along because someone said that all the stories were told with puppets, and that all the hymns usually reserved for school assemblies would be accompanied by guitar. (I had a very sheltered childhood and that seemed intriguingly novel.) At the time it seemed fun and friendly, but I didn’t go to more than a couple because I felt very out of place. I shouldn’t have, as I knew several of the other children there and I was familiar with the fables and bible stories being so cheerfully narrated, but even then I just didn’t feel like my faith fit their formula. I very much enjoyed Religious Studies at school, but didn’t ever feel compelled to sign up to any of the religions we covered. I liked bits from them all, and for me that was good enough. In many ways it still is, though I put more faith in science and people than I do much else. That said, I still have room in my life for some spirituality, and like the “safety net” of thinking that there is something out there in case I screw up. I don’t need to analyse it or explain it, and don’t feel the need to probe it further. People of faith often have some difficulty with this, because they want me to commit to one or other god/religion, and seek to categorise or convert my non-specific ‘hope’ into a tried-and-tested ‘belief’.

Partly because of this unsuitability, I had mixed feelings when the church got back to me at the end of November with a list of seasonal suggestions for helping out over the holidays. The opportunity they offered was perfect in so many ways; so local it was within spitting distance of the house, on Boxing Day so that I didn’t have to leave my grandmother alone at Christmas, and it was an event for lonely and disadvantaged residents (which, due to my Social Worker gene, pleased me more than the convenience). I was apprehensive though, because I remembered how out of place I had always felt there – and was fully aware that I hadn’t set a stiletto’d foot inside a church for more than a wedding, christening, funeral or carol concert in nearly a decade. The event they had organised was a Christmas service with carols, followed by coffee, a buffet lunch, and then an afternoon of entertainment, and was open to anyone with nowhere else to go; asylum seekers, the homeless, immigrants, singles, vulnerable people, and the elderly.

When arranging to help I had politely opted out of the morning service, and arrived later to prepare lunch and set the tables. The church has undergone major redevelopment recently, and is still only half-finished. I’ll admit to feeling a little overwhelmed by the now-unfamiliar building, and the sea of equally-unfamiliar faces whose accompanying names I’d forgotten almost before I’d finished shaking their hands. Putting my discomfort and the redundant introductions aside, I busied myself with the tasks set by the Leader of the Kitchen People. It was obvious immediately that the warm and approachable women in charge of today’s buffet had limited experience catering for charity. I grew up helping with the New Year’s Eve buffet at the Community Centre my grandfather ran, and helped with it almost every year from early childhood until his death when I was 19. Whether it was gathering balloons, buttering bread or – my very earliest job putting hundreds of sausages on sticks – I’d participated in a lot of buffet-cooking on a budget. These ladies, though all very nice, obviously had not. The food was lovely, but the presence of a pack of luxury Organic Jersey butter meant that their inexperience of low-cost cuisine was rather telling.

Within minutes of my arrival I was slicing baguettes for the garlic bread, and it became apparent that the ovens were no longer working. (It became apparent because the electricity for the whole room shorted.) Wondering how there could be a smell of burning when the oven was out, it was soon discovered that the smoke was coming from the electrical socket the oven had been plugged into. Due to the building work, the electrical supply to the points in the kitchen hadn’t been connected, so the Leader of the Kitchen People had plugged it into a 13amp socket on a reel of the builder’s extension cables. This shouldn’t have been amusing, but a long-standing joke between friends and me has been that none of us are saintly enough for churchgoing, and would probably be struck by lightning if we ever entered one at all. As I was stood a couple of feet at most from the oven and power-socket when it burst into flames, a little corner of my smoke-blackened soul wanted to jeer a triumphant “Ha! You missed!” in the direction of the church hall. More appropriately, I suggested that we take the trays of half-cooked food down the street to finish them off in my home oven, because the alternative was to serve little other than crusty bread and cherry tomatoes.

With lunch rescued and tables set, it was time to mingle with some of the event attendees, who were a very mixed – but over-all very lovely – bunch of people from all kinds of backgrounds. After coffee it was time for people to sit down to lunch. After my first gaffe – continuing to set Christmas crackers on the tables while they were saying grace, until I realised I should step back and stand still – lunch went pretty smoothly. Everyone was fed, and chatting to some of the other volunteers was nice. After setting out the food and making tea, I found myself seated between a particularly friendly couple who lived and worked locally and who were both fun, lively company, and a sweet Zimbabwean lady who had no family in the country. It was when chatting with the volunteers and other ‘regulars’ that I encountered the only nagging awkwardness of the day, which came every time anyone asked me which church I worship at, or asked how long I had been coming to theirs. Quietly saying that I am not a churchgoer and was just helping out seemed to satisfy some, and they were additionally thankful that I had spared my time for complete strangers. Others wanted a little more detail, and continued to advocate their different services to try and persuade me to join them. None were too pushy once I aired my Agnostic card, which I was pleased about. I had hoped to overturn the unfortunate stereotype all too commonly encountered in other religious folk, which involved any attempt to convert me, but was unfortunately unsuccessful. There was only one particularly dogged attempt to get me to come along to their services, but I think it backfired a little. I’d noticed a little leaflet placed on the table near me when she returned from fixing herself a coffee, but my only temptation to look at it came from the overwhelming desire to graffiti it. The leaflet had “The meaning of life is ____.” printed onto it in bold blue letters, and had I not been surrounded by disapproving people then I would have succumbed to the impulse to scrawl “42” in the blank space, a la Douglas Adams’ answer to the ultimate question in Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. While they were watching the film, I was sneaking a photo of the leaflet to announce my compulsion via Facebook as a way of preventing myself from fulfilling it in plain sight of the congregating Christians.

Not long after this, I was given the leaflet and told that it detailed an educational program designed to “explain Christianity”. She then asked me what I knew about the Alpha Course. Well, this presented the second point of awkwardness, because the only thing I really know about the Alpha Course comes from articles and documentaries by Jon Ronson, where he exposes the emotional manipulation behind the charismatic and persuasive approach, which at its zenith encourages speaking in tongues. I think she realised that I was unlikely to follow it up at that point, but I took the leaflet because I’d spent two hours wanting to do this:

A short clip where Ronson provides a brief but suitably sceptical description of the Alpha Course:

The entertainment for the day turned out to be not all that different to my Sunday School experience, as in the very same hall after lunch a man sat down with a an acoustic guitar, and vainly attempted to get people to sing along, before letting them play games instead. The only difference now was that instead of snakes and ladders they brought out a Nintendo Wii, which one of the younger volunteers attempted to teach a couple of old ladies how to play. The games were gradually replaced with quieter pursuits, as a handful of people settled into a game of scrabble, and everyone else relaxed into comfy chairs to watch a movie. Since puppets had been pivotal to my previous encounter, I was amused that the film chosen was Muppet Christmas Carol, bringing them to the fore once again.

Most people go to church to find God; whenever I go I find Jim Henson.

One older lady who was either Jamaican or Ghanaian giggled solidly throughout the movie, muttering to herself throughout the plot and gripping my arm while bent-double with laughter whenever any of the mice or Rizzo the Rat came on-screen. When it was over she asked if “the local library would have the book the film was made from” and asked who it was by. Considering that there is a Charles Dickens museum in Portsmouth, which faithfully recreates and preserves the house he was born in, it is uncommon to come across anyone who doesn’t know at least a little about the man. Dickens is such a traditional and iconic part of our local and national literary heritage that it was odd, for a moment, to find someone who was discovering him and his most famous Christmas tale for the first time. It was also lovely, because all the magic and laughter and emotion which I associate with my own childhood memories of the film was present in her experience of it, which was charming in its purity. She was thrilled with every scene, and completely wrapped up in the colourful cast of characters. It was a delight to witness, knowing as we explained Dickens to her that there was such a wealth of literature for her to explore next. Though if she’s hoping for a version of Great Expectations featuring Kermit as Pip and Miss Piggy as Estella, then I fear that she will serve only to confuse the librarian.

It was a very nice day on the whole, which succeeded in changing my Christmas routine enough that it was not only fulfilling, but far less strange. Before today my impressions of the local church had been limited to guitar music, puppetry, people trying to convert me, and a fear of catching fire. Now? Well… I’ll always associate it with sausage rolls too.

Wednesday, 13 October 2010

A Difficult Decennary

I don’t expect anyone to read this, but it needed to be written…

This week is a strange one for me. I’ve written before about how odd the annual anniversary of my surgery is, and how peculiar it always feels to remember back to an age when I was so poorly. This year I feel it more keenly than ever, as it marks a decade since an unassuming medical team at a local hospital saved my life.

At the time I knew things were bad, but had no idea quite how serious. Even now, looking back it’s all a topsy-turvy mess of memories and ridiculously warped perceptions. I recall how normal that alien situation eventually became – how necessity drove myself and my family to perceive some astonishingly awful trials as everyday occurrences, because in their familiarity they had become casual routine.

At fourteen years old I identified more with some of the younger parents than I did with the infants with whom I shared a hospital ward. Though deteriorating daily and desperate to go home, on one ward I spent my time chatting to a young mum whose toddler-daughter had been admitted following complications from her diabetes. I don’t remember her name, but I think the little girl was called Rebecca. The mother was young and had been raised within the mistrustful culture of many poorer cities, so was vary of the doctors and health visitors who had been trying to help her. The more she struggled with her daughters’ illness, the more help they tried to offer her, and the more worried she became that they’d take her Rebecca into care if they discovered she wasn’t coping. I remember long conversations where she’d tearfully recount the occasions when she had hidden in her flat with the little girl, trying to keep her quiet because a social worker was at the door, and the mother was scared even to let them in. They’d been alerted by the hospital because the pair had missed several paediatric check-ups. Rebecca’s mother said that the reason she had missed the check-ups were that she couldn’t always afford the bus fare to get her daughter to the hospital. Rather than asking for help, she had grown more and more fearful of displaying any weakness, lest it be used against her. After a few days of talking her round, and promising her that social services would be able to help her get to the hospital, and wouldn’t take her daughter away, the little girl was discharged and her mother promised me she’d take advantage of the help that was being offered.

A week later when Rebecca came to the hospital for a check-up her mother came to the ward with chocolates for me, her relief evident, the burden lifted somewhat from shoulders only a few years older than mine. She finally found the courage to break away from the scaremongering whispers of the council estate she grew up on, and allowed to social workers to visit her home and chat to her about her daughter. Together they’d sorted out the benefits she was entitled to, and helped her arrange travel for the little girl to the clinic.

I recount this because I remember it more clearly than I recall many of the details about my own circumstances. There was so much information buzzing about the place, so many people coming in and out, and so much crap to deal with (in both literal and less literal senses) that focusing on trying to make a difference became a way to derive some purpose from it all. My father reacted similarly to the situation, staying with me at the hospital the 9 weeks I was there, but putting in more hours than ever as unofficial social worker, grief counsellor and therapist for the many exhausted and struggling parents whose children were my contemporaries.

All the while time was ticking. We didn’t really know how fast at the time; not even the doctors knew how close I was going to come to being beyond their assistance. As I said, so much became normal that I stopped complaining about the pain, I just learned to get on with it. Daily rituals became learning opportunities for me and for the staff, who were more used to caring for younger children and made the most of the opportunity to finally converse with an articulate guinea-pig. They all wanted to know if I could feel the crushed tablets going down the nasa-gastric tube, and what the high-calorie feed tasted like, if I could taste it at all? I vividly remember the strange coldness as they’d flush the pills down with clean cold water to avoid the tube blocking, and the weird release of pressure following a little extra force when it did block, which made my stomach gurgle and made the gentle nurses wince.

My life revolved around various escape plans. Most days that meant that I would have my Dad or other visiting family take me down to the canteen where we’d try and spot presenters and producers from City Hospital, with whom we all became quite friendly. Other times it meant sitting in the Burger King in the hospital foyer, trying to collect all the Pokemon toys and dreaming up schemes to claim the most-coveted Pikachu. (Which we knew was selling for a lot of money on Ebay but could never persuade the staff to let me have.) Even if it was freezing cold I’d insist on going out to the fish-pond outside the main entrance, where I’d sit and nibble home-made sandwiches brought in by my Nan; throwing the fat, ethereal koi carp more than I ever ate myself, and occasionally chucking in a penny with a wish. The main escape plan however was a burning desire to go home – a desperate need which found me sobbing and desolate on more occasions than any physical suffering ever did. I made it home twice during that long stay, once for 14hrs, and the second time only for 7. Each time I’d persuaded the doctors that I was feeling a bit better and they’d given in to my begging to go home. Each time my condition worsened drastically from just the effort required to leave the hospital, and I was rushed back in by ambulance. The last of those times I remember what a treat it was to be pushed around our small local Tesco in a red cross wheelchair, picking out the food I’d been craving while incarcerated on the Children’s Ward. I’d been on a high-calorie diet for months and was encouraged to eat all the things most children are strictly rationed, but hospital food was forever lacking in flavour or nutrition, and the canteen also had its limitations. The meal I chose for my dinner was a puff pastry chicken pie; a pre-hospitalisation favourite and one I had missed the most during a brief period on a milk-free diet where pastry was forbidden. So pleased was I to sit down to this highly-anticipated meal that I – unusually – devoured my portion with gusto, enjoying my food for the first time in almost two years, without worrying about the pain and sickness which would, inevitably, follow. I was devastated when it made me just as ill as I had been when admitted to hospital in the first place, because not only did it seem a cruel denial of something I had been looking forward to, but it was a very difficult defeat for someone as stubborn as myself to accept.

It was then that I knew, regardless of the doctors’ hopes and my own determination to be fine, that observation and maintenance was no longer enough. They needed to intervene and operate, despite the dangers of the surgery and the massive and invasive nature of the operation and its aftercare. Such a drastic step was it to request such a course of treatment that my doctor had me assessed by a pair of psychologists who had to certify that I did indeed understand the gravity of the situation and wasn’t looking for an “easy way out”. I knew it was dangerous, and I was as scared as anyone is when they face something so uncertain, but I also felt deep in my bones that it was necessary. I was exhausted, but more than that, I knew we had exhausted all the other options, and I didn’t have what it took to try them all again when they’d had no effect. I’d borne the difficulty of the 20hr per day tube feeds to keep my weight viable, and tolerated the 60-plus tablets I took each day, but no more. It had kept me alive, barely, but that just wasn’t good enough any more. So eventually, they operated. It wasn’t until later I found out that when they had opened me up things were worse than they had realised. Because I’d grown accustomed to managing the pain and other awful symptoms, they’d failed to spot just how far my condition had worsened. We were told that if they hadn’t operated when they did, I would have deteriorated so much within the next few days that the operation wouldn’t have done any good. Discovering that I came so close to losing my life before I’d even had the chance to take charge of it has always felt slightly unreal. I think I have always felt a little detached from that particular aspect because I was at an age where every teenager feels invincible, immortal, and had never lost anyone close to me. I had no understanding of death, let alone any comprehension of my own threatened mortality. I had known that dying was a possibility, but saw it as something which could happen – if all else failed – but I never believed that the doctors would fail. With every unsuccessful treatment followed the presentation of another. More tablets, a different diet, more invasive tests. It was a relentless merry-go-round but never one I had considered finite. The thought that they would eventually run out of ideas was one which never really resonated with me. Doctors were clever, authoritative figures who made people better. They’d always managed to sort me out before. Being the product of a school system where the people in charge are omniscient, omnipresent beings who must be obeyed meant that I didn’t question the ability of those in charge of my case then. Providing I did as I was told I would get better. And I did as I was told most of the time. I argued with the doctors when they refused to explain treatment plans to me satisfactorily, but compromised in the end. Bar the occasional tablet flushed down the sink or thrown out of the window in exasperation (I blame myself for a generation of mutant pigeons on the south coast) I complied with every round of treatment eventually. Which was why they finally operated, despite the risks, when I asked them to. It proved to be a far from easy option, but one I cannot regret because it saved my life.